On a sunny day in early September, I voluntarily visit District 12. Of the 13 districts in Panem, the post-apocalyptic world of Suzanne Collins’ hugely popular Hunger Games series, District 12 is the smallest and poorest. Most of the district’s less than 8,000 residents work in Appalachia-like coal mines and if I close my eyes, I can picture them: Covered in detritus from a long day underground, they slowly shuffle back to their ramshackle homes.

Katniss Everdeen, one of the district’s teenagers, is on her way into the woods to hunt, a necessity in a district that Collins describes as a place “where you can starve to death in safety.” Other residents hang their heads and avert their gray eyes, conditioned by years of exploitation and oppression by the corrupt Capitol.

District 12—and Katniss Everdeen—may not exist, but in its heyday, the Henry River Mill Village was not much different than its silver screen counterpart. Located near Hildebran, North Carolina, in the foothills between the mountains and the piedmont, the village was home to a cotton mill for the first half of the 20th century. When the mill closed in the 1960s, the modest homes and buildings were abandoned. In 1977, a lightning strike started a fire that destroyed the mill completely.

Like other relics of a different time, the Henry River Mill Village may have crumbled completely if Hollywood hadn’t come to Hildebran in 2011 in search of a home for its Hunger Games heroine. After the first of four Hunger Games movies premiered in March 2012, fans from all over the world began flocking to western North Carolina in search of the village that doubled as District 12.

In October 2017, Calvin Reyes and his family purchased the property and formed the Henry River Preservation Fund. They plan to renovate, restore, or rebuild most of the village’s buildings with funds raised from sanctioned tours, events, and film and photo shoots.

Snakes and bottles

My tour begins inside of a temporary trailer in the parking lot of the village’s company store, which functions both as an office and a makeshift gift shop. The air conditioning is a welcome respite—it’s early in the day and late in the summer, but the heat and humidity are already oppressive.

I’ve read the books and seen the movies, but I’m not a Hunger Games super fan (a separate company offers an “unofficial fan tour” of the site, which includes archery practice). I’m not worried when Taylor Edwards, Henry River Mill Village’s site director, warns me that his tour will include “more history than Hollywood.” During the hour-long tour, Edwards, who is in rehearsals for a local production of the rock musical Hair, ends up providing a perfect mix of both.

A colorful wall inside one of the homes. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A rusted sign. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A fireplace inside one of the abandoned homes. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Most of the homes were duplexes. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Behind Edwards’ desk, Dwight—Henry River’s self-proclaimed archeologist—fastens snake guard shields over his shins (a non-poisonous snake recently surprised visitors inside of Katniss’ house). Dwight’s grandfather worked at the mill and whenever the weather is amenable, he suits up and heads to the banks of the river. He pierces the land with his pitchfork, looking for bottles and other buried treasures. He recently found a bottle near his grandparent’s former home stamped with the year they got married.

Edwards says they are keeping anything of historical value for a future museum, but hope to begin hosting bottle sales to unload the rest. Dwight’s passion for bottles—and the village’s dump—is seemingly endless. “He digs everywhere,” Edwards says.

A dam and doogaloo

Most everything Dwight unearths is from the early 1900s; between the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, not much happened along the banks of the Henry River. Land wasn’t worth much if it couldn’t be farmed. “This is really, really, really bad farmland here at Henry River,” Edwards says. “It’s very steep, and large scale farming just doesn’t work.”

The Civil War broke up the South’s agrarian slave system and ushered in a new age of industrialization. “All of a sudden this goes from being a dead place to boom,” Edwards says. “It’s the perfect place to build a mill.”

Sensing an opportunity, two prominent North Carolina families, the Aderholdts and the Rudisills, joined forces and purchased 1,500 acres of land surrounding the river. In 1905, they established the Henry River Manufacturing Company, the centerpiece of which was a three-story brick mill building. The village included 35 worker houses, a boarding house, a bridge, a dam, auxiliary storage buildings, and a company store.

“Doogaloo” coins were only good in the company store. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The pastries sign was replaced recently when the original was stolen. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The Henry River Mill spun cotton into yarn. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

The mill turned raw cotton into spools of yarn used in embroidery and fine lace. Because the Aderholdts and Rudisills owned much of the surrounding land, the workers were isolated. The business was “the only game in town,” Edwards says, and 450 workers lived just up the hill from the river in small houses provided by the company. They were paid in “doogaloo” coins, a special currency accepted only at the company store.

The store functioned as a de facto downtown and once included a post office, bank, church, and school. Edwards likens it to Target: “What can you get at Target? Everything. From Kleenex to clothing to Clorox to coal,” he says. “That was the company store.”

The building was constructed quickly with sun-baked mud bricks made from the banks of the Henry River on a foundation of river rock. Although the bricks are chalky and brittle, the building has survived more than a century of lightning strikes (including at least two direct hits), hurricanes, and tornadoes. The river’s dam, once used to generate power for the mill, is currently strewn with fallen trees and debris from a recent flood, the county’s third worst on record.

District 12

In 1975, Wade Shepard purchased 72 acres of the property, including the 20-plus buildings that were still standing. The 1977 fire destroyed any plans he had to revitalize the mill. When the village was chosen to represent District 12, the production company partially renovated house number 16 to use as the residence of the Everdeen women: Katniss, her younger sister Prim, and their mother. It’s the only building visitors can safely enter.

The company store became a bakery, owned by the family of District 12’s other Hunger Games tribute, Peeta Mellark. Reyes understands the movie’s continued appeal and ability to draw crowds. He has plans to turn the store into a restaurant, but for now it still looks as it did in the film (when the original “Pastries” sign was stolen, it was quickly replaced with a replica).

The Everdeen house. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A bed inside the Everdeen house. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan In 2011, the village was transformed into District 12 from the Hunger Games. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

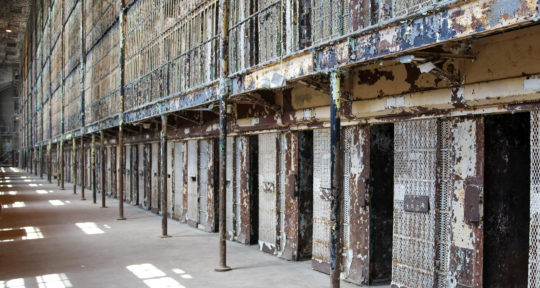

About half of the workers’ houses are still standing in various states of decay. The mill village was separated by class; workers ranked the lowest and lived in duplex-style houses with a living room in front, a kitchen in back, and a bedroom on the second floor. “If you thought the house was small, joke’s on you—you only get half of it,” Edwards says. Five of the slightly larger homes were inhabited by supervisors. High on a hill across the river looms the grand former Rudisill mansion.

When I peek through open windows I see couches, fireplaces, and piles of debris. Paint peels off surprisingly colorful walls and a rusty sign posted above the front door of one structure advertises used furniture and appliances for sale. A giant cistern, once used to protect the mill from fire before a sprinkler system was installed, is now fenced off to protect visitors. An ornate turn-of-the-century fire hydrant rises from the ground like a sculpture dedicated to the area’s industrial past.

Macabre mill

It was still Shepard’s private property in 2012, when fans of the movie began to appear in droves. “People would come out here and depending on [Shepard’s] mood he’d say, ‘Yeah, you can walk around,’ or, ‘No, get out,’” Edwards says. Not much time passed before Shepard put the village up for sale. “I still consider it a good investment,” he told CNN in 2012. “If I was [younger] I wouldn’t be selling.”

Shepard died in 2015, and in 2017, Reyes discovered the village. “I called my mom immediately and said, ‘I love this place. We have to buy it,’” he told the Citizen Times. “It needs to be saved and brought back to life.”

The village hosts events all year, including Santa meet-and-greets in December, Mill Village Fest in May, and haunted tours in October. On October 26, the village will host a Halloween party called “Boos & Brews,” featuring a costume competition, flashlight tour, a beer graveyard, food trucks, a dance party, and spooky storytelling with the paranormal group Soul Sisters.

A turn-of-the-century fire hydrant. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The workers lived just up the hill from the river bank. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan “No trespassing” sign on the mill’s original road. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

A lot of the “history” relayed on other ghost tours is suspect, but Henry River Mill Village doesn’t need to embellish. Over the past century, “actual people were murdered or kidnapped here and countless people lost fingers in the mill,” Edwards says. “ A lot of our history is actually quite macabre.”

In addition to the restaurant, Reyes hopes to restore the homes and make them available for overnight stays. But the first step is to pick up where Hollywood left off. Construction on house 16 is set to begin soon, with plans to turn it into a museum. “We want this to be a hub in North Carolina,” Edwards says.

If you go

Historic tours of Henry River Mill Village are offered Thursday through Monday at 10 a.m., 12 p.m., 2 p.m., and 4 p.m. Boos & Brews takes place on Saturday, October 26 at 6 p.m., rain or shine.