For Thea Haver, a love of architecture runs in the family. “My mother’s mother wanted to be an architect—a dream dashed by having three kids,” she says. “Instead, she’d strap the kids into her car and drive them around to get her architecture fix.”

Years later, as a transplanted Baltimorean living in Albuquerque, Haver would leverage this family-instilled architectural appreciation to found Modern Albuquerque, an educational nonprofit, with her husband, Ethan Aronson. Today, the pair works to promote, preserve, and educate the public on Albuquerque’s unexpected abundance of mid-century modern architecture and the fascinating, often untold stories that come with it.

Form vs. function

Dating back to the “post-World War II, pre-Star Wars era” between 1945 and 1975, modernist architecture is, as Haver describes it, a specific set of principles where form follows function. While mid-century modern architecture often incorporates aesthetically beautiful elements such as glass curtain walls, expressive rooflines, and raw stone and tile facades, Haver says that style alone generally isn’t the intention of a modernist design—these buildings are doing a job.

One of the most well-known examples of modernism’s principles at work in Albuquerque is the iconic First National Bank east tower, a glimmering, 17-story skyscraper located at the corner of San Mateo Boulevard and Central Avenue. Jutting out from an otherwise ordinary skyline of single-story buildings and commercial storefronts, the gold ceramic tile on the building’s exterior reflects the desert sun back onto drivers motoring into the city along historic Route 66—a sight both beautiful and surprising.

“The tower was built with the desert environment in mind,” Haver says. “It’s a visual display of wealth that clues us into the building’s original purpose: to house a bank.”

But wealth wasn’t the only message that the designers and architects aimed to communicate through the building’s exterior. Shattering the record for the tallest building in New Mexico upon its completion in 1963, the First National Bank tower was intended to become the hub of a new commercial district along Route 66—an idea that, unfortunately, never materialized. As super highway I-40 drove Albuquerque’s residential expansion farther eastward, the area surrounding the building fell into economic decline shortly after its construction.

“I refer to it today as a ‘monument to faded optimism,’” Haver says. “But the placement of these architectural resources along Route 66 heightens their visibility and significance to the community. They’re among the first things that visitors see, and they represent a slice of the city’s past.”

A mid-century hotspot

Despite its unfortunate timing, the First National Bank east tower helped spark curiosity in Haver upon her arrival in Albuquerque in 2014. “I frequently explain how surprised I was about the diversity of architecture in Albuquerque when I first landed here,” she says. “Diving in was an enthusiast’s dream.”

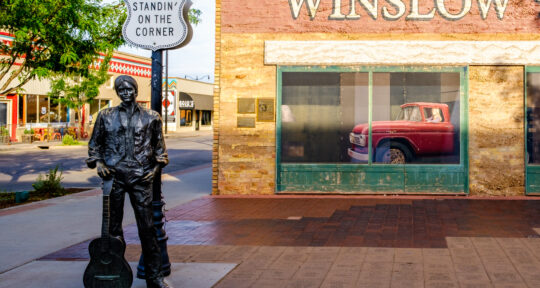

A major stop along historic Route 66, Albuquerque has a long-standing history with road travelers and tourists alike. The city is currently home to the longest continuous stretch of Route 66 within a single city (18 miles), and is the only place where it’s possible to stand at the intersection of the highway’s first and second alignments. As such, Route 66 nostalgia is a major driver of Albuquerque’s tourism—though Haver is quick to point out that it’s certainly not all that the city has to offer.

“Sometimes people come to Albuquerque thinking that Route 66 is all there is here, or that there’s nothing new to be said about it,” she says. “Neither could be further from the truth.”

Noticing this limited awareness, specifically regarding Albuquerque’s mid-century modern architecture, Haver and Aronson got to work. The pair began conducting original research on standout modernist sites around the city, speaking with current and former preservation planners, architects, developers, business owners, realtors, designers, and archivists to piece together Albuquerque’s storied past as a hotspot of mid-century modernism.

“The research process was messy at first,” Haver says. “Albuquerque’s planning department didn’t hold onto building permits from this period and records were strewn across the city, if they existed at all.”

Haver and Aronson finally launched Modern Albuquerque in 2018, after years of research, networking, planning, and plenty of investigative digging. As a go-to resource for anyone interested in the city’s abundance of modernist architecture and public art, Modern Albuquerque functioned as equal parts tour company and research organization in its earlier days. They offered walking tours to the public and continued their research on buildings to add to the city’s pre-existing inventory of modernist structures. As of May 2020, the Modern Albuquerque team has helped increase the inventory of historic modernist buildings to 366 structures in total—with plenty more on the way.

“Focusing on the buildings and their stories has helped us to renew interest in architecture among residents,” Haver says. “At stoplights, people tell us that they are now looking around to notice what’s there, as well as what isn’t. That kind of awareness is a small step toward preservation.”

Preserving untold stories

Today, Modern Albuquerque focuses more on a proactive approach to preservation, while personal tours are on pause due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Among a plethora of other ongoing projects, Haver says that the team has already started preemptive catalog work on post-1975 structures, while an expansion to sites beyond Albuquerque’s city limits may also be on the horizon.

“So far, we’ve only catalogued buildings in Albuquerque, but we keep informal tabs on sites outside the city limits,” she says. “We were shocked to find out that there are at least two streets within the Santa Fe city limits lined with mid-century modern homes—no one tell city planners!”

Modern Albuquerque recently launched a new website that features a downloadable map of “must-see modernism” throughout the city of Albuquerque—perfect for locals and visitors alike looking to craft their own driving tour itineraries along old Route 66 or beyond.

“Route 66 has this mythic quality to it,” Haver says. “People come from far and wide to drive it, but even on this well-documented road, there are untold stories.”

Lesser-known stories are exactly what drives the need for preservation in any city, but for a Route 66 town, it’s especially important. Without someone calling attention to the importance of these structures, their architecture, and the treasures that lie within, we risk losing them—for good.

“If we don’t know everything about what’s on Route 66, what else don’t we know?” Haver says. “What else could be out there, and what can we keep from being lost before it’s too late?”