A visit to Washington, D.C. can make a person feel small. Surrounded by huge, imposing government headquarters and larger-than-life sculptures of our country’s founders—and their even loftier ideas—it’s easy to lose perspective. But less than three miles east of the long shadow cast by the Capitol’s famous dome, tucked away in the middle of the 446-acre U.S. National Arboretum, is a place designed to help visitors reset and reconnect with nature: The National Bonsai and Penjing Museum.

For most people, the word “bonsai” probably brings to mind an image of a miniature tree, pruned into submission. While this isn’t entirely inaccurate, the Japanese art of bonsai—and its Chinese counterpart penjing—is far more complex.

The National Bonsai and Penjing Museum not only showcases more than 100 specimens—some of which predate the founding of our country by centuries—but it also exists to educate future generations about the ancient art form. The collection is divided into region of origin and includes trees from Japan, China, and North America. The open-air museum, which began to take shape in the 1970s, was the first of its kind in the world.

“Bonsai is about providing a window into nature,” says Felix Laughlin, co-president of the National Bonsai Foundation, in a video about the museum. “It has a magical quality.”

In 1982, the National Bonsai Foundation was formed to help support and further the mission of the museum. Although the number of people visiting the museum has increased throughout the years, the National Arboretum still feels like an undervalued D.C. destination. It may not be conveniently located near a Metro stop, but a visit to the beautiful grounds is worth far more than the cost of admission, which is free.

Bone-sigh

Bonsai (pronounced bone-sigh), very loosely means “tree in a pot” or “planting in a pot.” Although the word is Japanese, the horticultural practice originated in China. As far back as 700 C.E., the Chinese were using special techniques—called “pun-tsai,” or “tray planting”—to grow small trees within containers. These tray landscapes were brought to Japan and became popular along with the spread of Zen Buddhism.

“Finding beauty in severe austerity, Zen monks—with less land forms as a model—developed their tray landscapes along certain lines so that a single tree in a pot could represent the universe,” according to Bonsai Empire.

After WWII, soldiers who had learned about bonsai overseas returned home and interest in the tiny trees began to flourish in America. Like the famous flowering cherry trees that surround the tidal basin, Washington D.C.’s bonsai collection began with a gift from Japan.

Former museum director Dr. John Creech, who traveled the world in search of interesting plants, was the first to suggest that a gift of bonsai would be appropriate to celebrate America’s bicentennial. In July, 1976, The Nippon Bonsai Association gifted 53 bonsai trees to the U.S. National Arboretum.

Creech, who greatly underestimated the size of the gift, arrived in Japan with two empty suitcases. Archival footage shows the trees being packed instead into nearly a dozen large wooden crates. The elaborate dedication ceremony was attended by then-Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger.

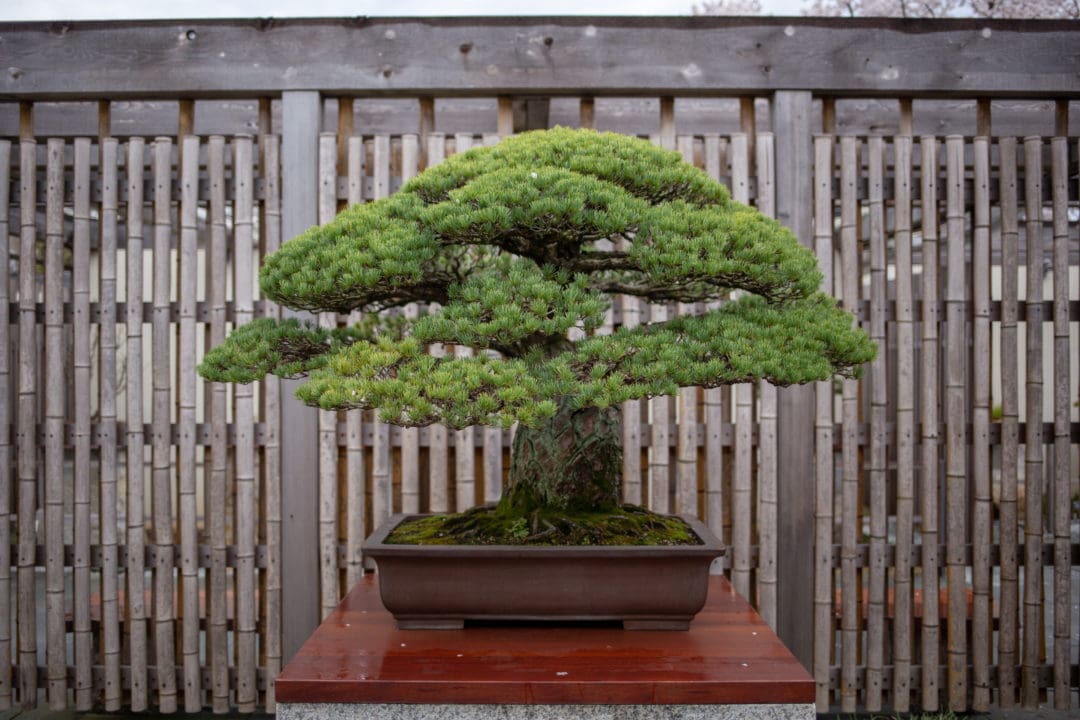

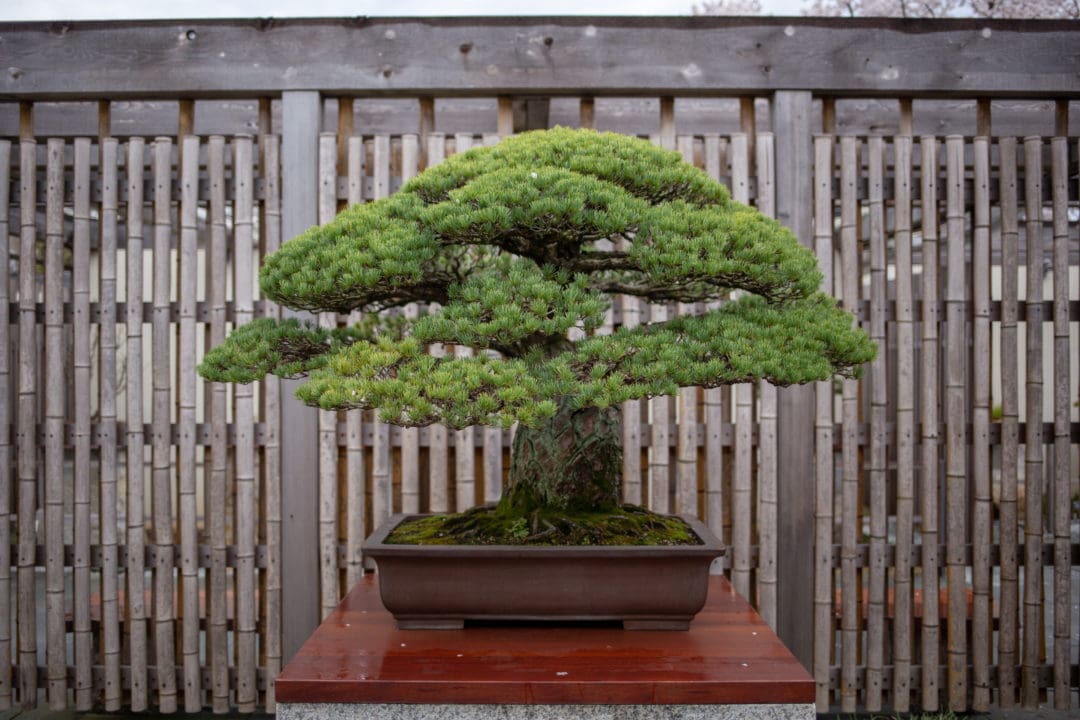

One of the original 53 trees—the Imperial pine—has been in training since 1795. It’s one of two identical trees that once flanked the Imperial household in Japan. Japanese emperor Hirohito gave one tree to U.S. and kept the other in Japan.

More than simply sharing a cultural tradition, the gift was a symbol of peace and the promise of continued friendship between two nations who had been at war with each other just 30 years earlier. “A gift of bonsai is a gift of peace,” says Laughlin.

Hiroshima and Goshin

Peace between the U.S. and Japan did not come without consequences. On August 6, 1945, the Japanese city of Hiroshima was devastated by an atomic bomb. It is estimated that 30 percent of the city’s population—nearly 80,000 people—were killed by the blast and subsequent firestorm. Almost five square miles of the city were destroyed, reducing more than half of its buildings to rubble. A Japanese white pine tree belonging to the Yakami family was among the survivors.

The tree—in training since 1625, and the oldest in the museum—has been in the Yakami family for six generations. Part of the original 53 trees, it was gifted to the museum by bonsai master Masaru Yakami. Even though it’s no longer in Japan, the white pine is still visited by members of the Yakami family.

The Chinese pavilion showcases the museum’s collection of penjing, which is more freeform and less serious in its execution than bonsai. Penjing trees often have their roots draped over rocks or include small figurines. Shaping trees into the shape of an animal, particularly one of the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac, was also a popular penjing practice. Many of the trees sit in ceramic containers that are more than a century old.

The tropical conservatory houses both bonsai and penjing made from tropical and sub-tropical species. A bonsai library houses a collection of rare books and the museum has a collection of more than 100 viewing stones, a lesser-known art form closely-related to bonsai.

According to the museum, “While a bonsai is cultivated to evoke the qualities of a venerable old tree, a viewing stone is usually displayed to suggest an aspect of the natural landscape, such as a distant mountain or a waterfall. Thus, when these small-scale forms are viewed together in a complementary arrangement, the whole of nature can be imagined.”

But the most famous bonsai in the museum’s collection is in the North American pavillon. Goshin (which means “protector of the spirit”), in training since 1948, was created by John Naka, the most famous bonsai master in the U.S.. Naka helped elevate the popularity of bonsai in the western world and—until his death in 2004—he came to the museum once a year to help maintain his trees. Goshin is a Chinese juniper forest planting comprising eleven trees, each representing one of Naka’s grandchildren.

An investment in the future

Most of the time, our pets die before us and our hobbies die with us, but given the proper care, bonsai can last for centuries. Although the ages of some of its trees are unknown, the museum has bonsai that have been in training since the 1600s, 1700s, 1800s, and 1900s. To begin a bonsai is to take a leap of faith and make an investment in the future.

“In general, caring for the trees is a very involved, very delicate art form,” says Travis Hare, who handles PR for the foundation. “Many of the trees on display have been around for hundreds of years, handed down from generation to generation before one day finding their way to the museum.”

It’s this longevity that makes the education of future generations a crucial part of the museum’s mission. In early May, the Potomac Bonsai Foundation, The National Bonsai Foundation, and the National Arboretum join forces for the PBA Bonsai Festival. The celebration includes workshops and demonstrations for both bonsai veterans and newcomers. Attendees can create their own bonsai, or simply admire the work of others.

The art of bonsai isn’t as mysterious as it may seem—novices should be patient and attentive, but not intimidated. Like almost any plant, the trees need to be watered, fertilized, pruned, and transplanted.

“As they take care of the bonsai over the years, a special bond develops between the caregiver and the bonsai,” says Laughlin. “This love and bond expands to include all of nature.”

There is at least one caretaker on staff at the museum 24 hours a day to make sure the trees are getting the attention they need. More than anything, it’s this constant devotion that makes the age of the trees impressive. As we live lives that often seem frustratingly short in a world that can feel much too large, caring for bonsai can connect us to where we’ve been—and provide a hopeful view of the future.

These small-but-mighty trees have survived the worst of humanity, including war, atomic bombs, and time itself. Living witnesses to history, they may outlast their owners, but they stand today only because of someone’s love, dedication, and patience.

“People have been taking care of these trees every day for hundreds of years,” says Laughlin. “It’s quite a legacy to have here.”

If you go

The National Bonsai and Penjing Museum is open every day from 10:00 a.m.- to 4:00 p.m. The Arboretum and the Museum are closed on New Year’s Day, Martin Luther King’s Birthday, President’s Day, Veteran’s Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. Admission is free.