A wooden bench located across the street from the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum is painted in bold white letters proclaiming that Baltimore is “The Greatest City in America.” Twenty-five years ago, I moved from Baltimore—a working class city steeped in Black history—to New York City. But during the COVID-19 pandemic, a family emergency beckoned me home for an extended stay.

Despite being “a hard town by the sea,” as Nina Simone sings in “Baltimore,” the bench’s positive message is how I hope visitors view my hometown. That optimistic spirit is very much alive at the 17,500-square-foot wax museum, which spans several refashioned row homes along East North Avenue in East Baltimore.

My first trip to the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum was at the beginning of my career as a reporter for The Baltimore Afro-American newspaper. It was a unique educational experience, but during my second visit—as 2020 comes to an end—I see the exhibitions through more mature and woefully woke eyes.

“Our history didn’t have faces”

Founded by husband and wife educators Dr. Elmer P. Martin and Dr. Joanne Martin, the museum uses incredibly detailed, life-size wax figures and artifacts that share the African American experience from ancient Africa and slavery to the present.

Up until his untimely death in 2001, Elmer Martin was a professor of social work at the historically Black Morgan State University. The museum was inspired in part by the disillusionment he felt by his students rejecting their roots.

“My husband especially was very much a product of the Black Power and Black consciousness era,” explains Joanne Martin. “He came to the conclusion that we failed to build institutions designed solely for the purpose of preserving our history and our culture. [So] every generation was going to have to start from scratch.”

After a trip to Potter’s Wax Museum in St. Augustine, Florida, the couple saw an opportunity to preserve and showcase Black culture in an innovative way.

“I was just fascinated by the whole notion of a wax museum and the possibility of telling the story that way,” Martin says. “For me, our history didn’t have faces.”

The first Black history wax museum

Similar museums exist, but the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum—with 150 figures currently on display—is hailed as the first and most comprehensive.

“We have learned so much over the years about how to craft an exceptionally made wax figure,” says Martin. “I now guide the process and pride myself on how proficient I have become in seeing details the novice would miss.” She designed the newer images of a seated Frederick Douglass, with his impressive mane of hair, and gospel great Mahalia Jackson, captured mid-song with eyes raised to the heavens and her hands clasped.

Prior to opening the museum in 1983, the Martins had a traveling exhibition of four wax figures they displayed in shopping malls, schools, and churches: their first statue of Douglass, educator Mary McLeod Bethune, white abolitionist John Brown, and slave revolt leader Nat Turner. The original wax figures cost $4,500 each—today they can be as much as $25,000.

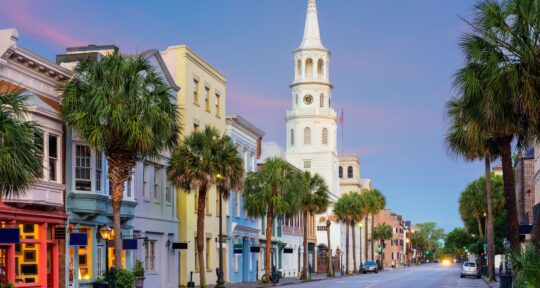

The museum’s original storefront in downtown Baltimore housed about 20 wax figures, and Martin pawned her wedding rings to pay the rent. In 1988, the couple moved the museum to its current location in the 1600 block of East North Avenue, hoping to bring tourism to a disenfranchised area of the city.

“Conventional wisdom all over this nation is that you hide your poverty areas. And once you succeed in hiding them, then you can succeed in neglecting them,” says Martin. “But [we decided] to create a museum right in the heart of the African American community and to show that tourism can thrive.”

From slavery to freedom

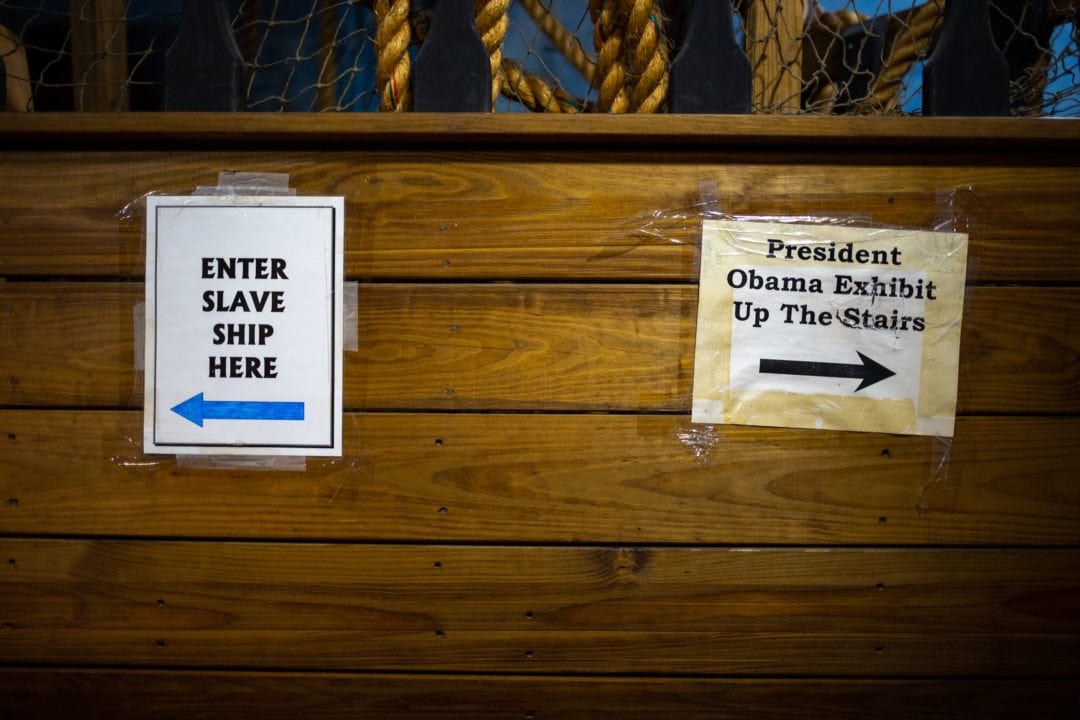

During my visit on an overcast November morning, the first exhibits I encounter are “Horror of Captivity” and “The Slave Ship,” both harrowing illustrations of the transatlantic slave trade.

My enslaved ancestors were stolen from their homeland, separated from their families, stripped of their language and cultural identity, tortured, and beaten into submission by their evil captors. As I descend the stairs into the replica slave ship, I’m greeted by forlorn figures of men, women, and children chained together and stacked in cramped quarters alongside vermin and corpses. I’m saddened and angered, but I also feel a sense of pride. A less resilient people might not have survived the Middle Passage; at an interactive station I pour a libation in honor of the countless brave souls who came before me.

At every turn, I witness how African Americans have flourished in the face of insurmountable odds. Stoic wax figures showcasing Black excellence include prominent civil rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, groundbreaking Marylanders Douglass and Harriet Tubman, North Pole explorer Matthew Henson, and Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall.

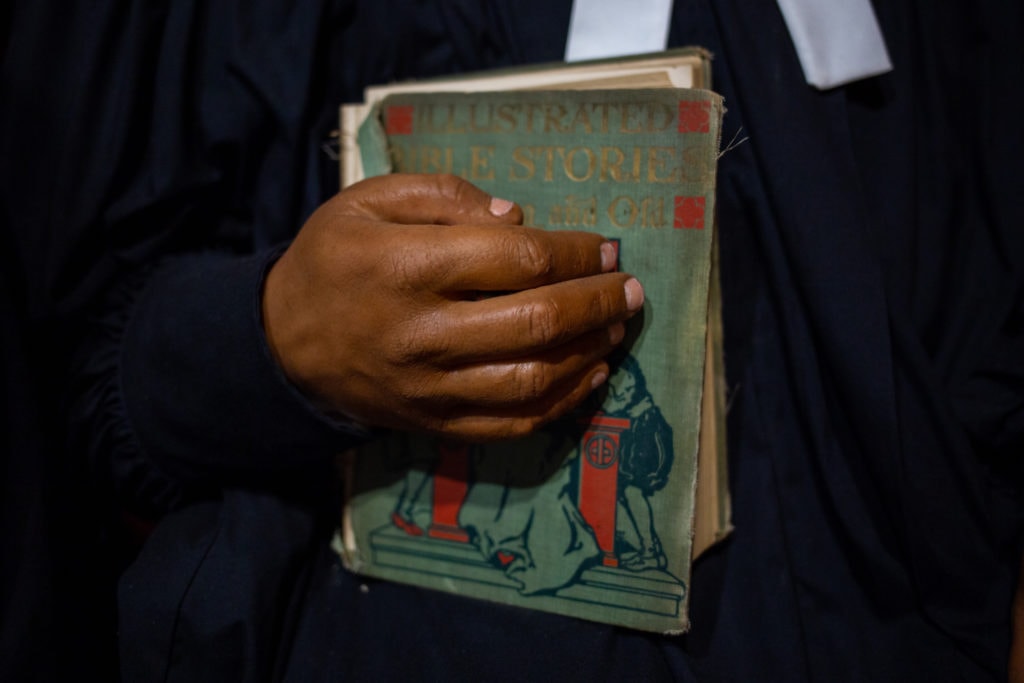

Blacks in the arts are also celebrated, including singer Billie Holiday, writer James Baldwin, and Baltimore teacher and storyteller Mary Carter Smith. One of the most recent additions is the “Walking in the Footsteps of Our Ancestors” exhibit, which features a statue of the first Black president of the United States, Barack Obama.

To show youth from the surrounding Oliver community that they can excel and rise above stereotypical assumptions, Martin implemented a training program for high school students to become museum and tour guides.

“So much of what gets written about Baltimore is negative. But I haven’t met any children who make me think of the negatives,” says Martin. “These amazing children come through the museum, become involved, and walk away understanding the power of history.”

Never forget them

Housed in the museum’s basement, a graphic lynching exhibit comes with a parental advisory warning. It’s distressing to view photographs of grinning white crowds gathered around hanging and dismembered Black bodies, but the Martins were adamant about not “whitewashing” history. They felt a permanent lynching exhibition was necessary. As I descend the stairs, I see a framed sign that reads, “Identify with the victims and martyrs, and never forget them. But do not get bitter or despondent over what they endured.”

Plaintive poems and newspaper articles detail the atrocities and memorialize victims. In 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till was visiting family in Mississippi when he was kidnapped and brutally murdered by a mob of white men for allegedly whistling at a white woman. More than 65 years later—with the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and far too many other Black people at the hands of law enforcement and white supremacists—the legacy of lynching lives on.

Another sign encourages non-BIPOC visitors interested in earnest allyship to “Get angry over the oppression that Black people and other oppressed people are still suffering today; and put yourself in a position to resist now as your ancestors did back in the day when lynching was a national past time as popular as baseball games and circuses.”

If you go

Although plans for expansion have been put on hold due to COVID-19, The National Great Blacks in Wax Museum is currently open Thursday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Face masks are required for entry. The museum is closed on select holidays, including Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, and New Year’s Day.