“Any day above ground is a good one,” according to the National Museum of Funeral History in Houston, Texas. The museum’s exhibits range from hair art to hearses, and serve as a reminder that, as Benjamin Franklin once said, “In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” A visit to the museum makes it clear that no one—not presidents, celebrities, or popes—are exempt, at least from the former.

“Death has been in our faces more than anything this past year,” says Genevieve Keeney, a licensed funeral director and the museum’s president. “You can evade taxes, but you can’t evade death. The Grim Reaper will definitely get you.”

Yes, the National Museum of Funeral History focuses on death—but it’s not depressing or creepy. The museum’s goal is to educate visitors on everything from celebrity funerals to the modern-day death care profession.

“People are surprised by the museum,” Keeney says. “There’s something for everyone. If you like cars, you’ll love the hearses. If you love history, you’re going to love this museum. People lose track of time here.”

Tools of the trade

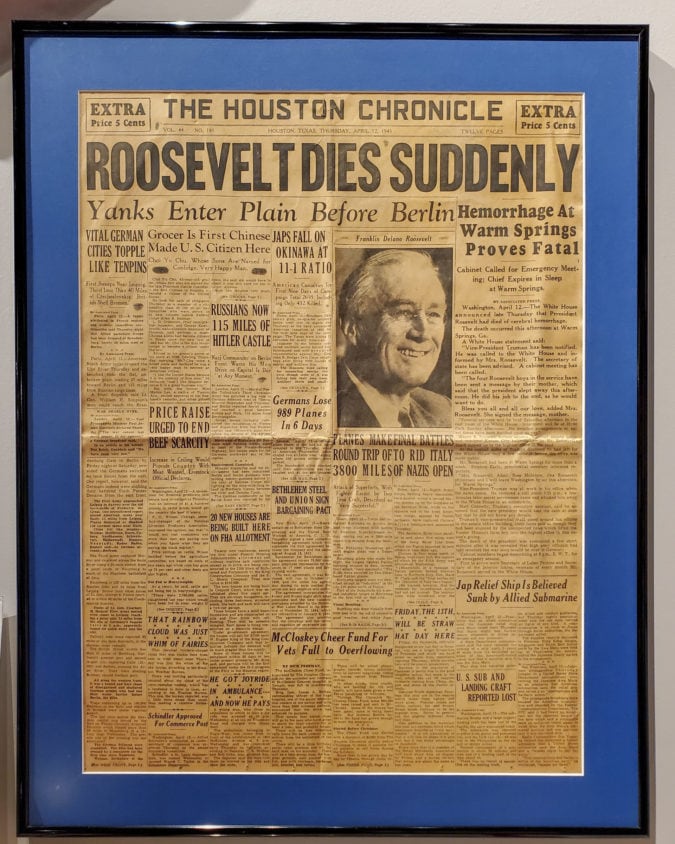

R.L. Waltrip founded the National Museum of Funeral History in 1992 with objects he discovered while expanding his family’s funeral business. Waltrip hated to think that the tools of his trade, including hearses and yellowing newspapers announcing a president’s death, would end up in a landfill.

The museum’s impressive presidential funeral display continues to grow in part because of the museum’s chairman, Bob Boetticher, a renowned mortician for several prominent politicians. Boetticher has orchestrated funerals for Presidents Ronald Reagan, Gerald Ford, and George H.W. Bush, as well as four first ladies, Senator John McCain, and many others.

Displays and memorabilia in the permanent Presidential Funerals exhibit date as far back as the first one, George Washington’s in 1799. A bill including a eulogy delivered by Judge Minot in Boston and Washington’s $99.25 funeral bill ($2,052 today) are both on display. After Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865, mourning events lasted for weeks. As the first president to be embalmed—a process that was developed during the Civil War—Lincoln’s body was able to take a 14-day train trip from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Illinois, with stops for mourners to pay their respects along the way. “A lot of milestones in our industry are showcased in Abraham Lincoln’s funeral, including embalming and the funeral train,” Keeney says.

Mary Lincoln couldn’t bear to ride with her husband on the train, but she also didn’t want him to make the trek alone. So she had the remains of their son Willie—who died of typhoid fever three years prior, when he was just 11—exhumed. Willie’s coffin traveled next to his father’s on the trip.

Displayed in the museum is a photograph of Lincoln’s presidential-turned-funeral train car and a replica of the horse-drawn hearse used to transport the father and son to and from the train. Pointing to the hearse’s black plumes, Keeney says, “The larger the plumes, the greater the socioeconomic status. If a hearse with very large plumes passed by, everyone would know that was a very important person.”

Hair and hearses

The museum also has a lock of Lincoln’s hair cut off by Dr. Leale, the first doctor to arrive at Ford’s Theatre, so he could better examine the president’s wound. The wife of then-Speaker of the House (and eventual vice president) Schuyler Colfax snipped a lock too, giving it to Mrs. Lincoln. Saving a loved one’s hair for mourning jewelry or art was a popular Victorian tradition. The museum’s display of intricate hair art is the only exhibit that makes me uneasy, and I’m grateful this macabre tradition has fallen out of favor.

Displays from more recent years include replicas of President Kennedy’s and President Reagan’s caskets. The iconic images of John F. Kennedy Jr. saluting his father and a frail Nancy Reagan draped over her husband’s casket line the walls alongside other somber photographs.

The planning of a president’s funeral often begins as soon as the elected official takes office; Boetticher contributed a 597-page funeral plan for 38th President Gerald Ford. “The funeral, burial or cremation, who presides, and their final resting place are up to the family,” Keeney says. “But protocol dictates a president must lie in repose in the Capitol Rotunda.”

Along with Waltrip’s and Boetticher’s contributions to the museum, generous donors continue to add memorabilia to the ever-growing collection. The newest exhibit contains funeral programs, military uniforms, and clergy vestments from George H.W. Bush’s memorial service held at the National Cathedral in December, 2018.

No one gets out alive

Young, old, rich, poor, famous, infamous, or somewhere in between, “no one here gets out alive,” as Jim Morrison sang in the song “Five to One.” Morrison himself was no exception; he’s part of the museum’s Gone Too Soon memorial dedicated to the dozens of famous artists and actors who passed away at the age of 27. Other members of the “27 Club” include Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Amy Winehouse, and Anton Yelchin.

Kobe Bryant and Charlie Daniels, who both died in 2020, are the newest members included in the Thanks for the Memories exhibit. Their displays join beloved icons Judy Garland, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Marilyn Monroe, along with lesser-known names such as Arch West, a marketing executive with Frito-Lay’s credited with inventing Doritos.

The museum’s Celebrating the Lives and Deaths of the Popes exhibit teaches me more than years of attending parochial schools. According to Keeney, the most precious artifact in the museum is a sash worn by Saint Pope John Paul II. Similar to U.S. presidents, protocols and rituals dictate everything done after a pope’s death down to how to destroy the pope’s fisherman ring used to seal official documents.

Keeney’s personal favorite is the History of Cremation exhibit, which features information on how a loved one’s ashes can be transformed into keepsakes such as gemstones or art. As an example, a portrait of Keeney’s sister, made from cremains, hangs in the museum.

The museum’s collection of quirky caskets includes hand-hewn wooden fantasy coffins from Ghana that resemble everything from airplanes to animals. And for anyone wishing to disprove the notion that you can’t take your money with you, a massive casket covered with dollar bills shows that maybe you can.

As a car enthusiast, Waltrip’s favorite piece is a hand-carved 1921 Rock Falls hearse. It’s one of many in the museum’s meticulously maintained fleet, with pieces spanning more than a century of “hearse-tory.” A horse-drawn hearse features original plumes; interchangeable, carved wood ornaments eventually replaced the feather plumes, but the symbolism remained. Large ornaments meant that in the end, even the rich and famous couldn’t escape the Grim Reaper.

If you go

The National Museum of Funeral History is open—and following CDC guidelines on COVID-19—Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sunday from 12 to 5 p.m. The museum is closed on Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, and New Year’s Day.