Five miles northwest of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., you’ll find a 7.18-gram basalt rock from the Moon’s Sea of Tranquility brought back to Earth by the crew of Apollo 11. Under the same vaulted roof resides the remains of Woodrow Wilson, the 28th president and only former Commander in Chief to be buried in the District of Columbia.

Nearby sits a pulpit from England’s Canterbury Cathedral, a cross made from fragments of the Pentagon after September 11, 2001, and a stone from the Western Wall in Jerusalem. Soaring hundreds of feet above it all are 288 angels, 215 dazzling stained glass windows, 112 gargoyles, and grotesques carved in the likenesses of famous figures including Eleanor Roosevelt, Mother Teresa, Rosa Parks, and Star Wars villain Darth Vader.

These treasures aren’t housed in a Smithsonian institution, although they very well could be. They are part of the permanent collection of Washington National Cathedral, which first and foremost is still an active house of worship. Weekly services take place alongside sightseeing tours and special events, and although it was founded as an Episcopal cathedral, longtime docent Bob Magner says that one would be hard pressed to “find a faith that wasn’t represented” within the building’s thick Indiana limestone walls.

The idea for “a great church for national purposes” was first proposed by Washington, D.C.’s master planner Pierre Charles L’Enfant in 1791. More than a hundred years later, the cathedral’s foundation stone—part of which came from Bethlehem—was laid, followed by a speech from President Theodore Roosevelt and the Bishop of London. But L’Enfant’s grand vision didn’t fully come to fruition until 1990, when President George H.W. Bush acknowledged the completion of the west towers, saying, “God speed the work completed this noon and the new work yet to begin.”

Today, the 150,000-ton Washington National Cathedral is the second largest cathedral in the U.S. and the sixth largest in the world.

Download the mobile app to plan on the go.

Share and plan trips with friends while discovering millions of places along your route.

Get the AppLet there be light

I arrive at the cathedral on a sunny but frigid Thursday afternoon in late December. It’s less than a week until Christmas and dozens of people are hard at work draping poinsettias and evergreen wreaths on pulpits, tombs, and altars. Magner says that I’m lucky to have visited on a sunny day and I immediately see why. Light streams through the 26-foot Creation rose window’s more than 10,000 pieces of colored glass, scattering rainbow beams over the beige limestone. “The light changes every single day,” Magner says. Religious beliefs notwithstanding, it’s hard not to be awed by this literal interpretation of the Bible’s declaration, “Let there be light.”

Magner laments that it’s difficult to truly appreciate the craftsmanship and artistry that went into the cathedral’s more than 200 separate stained glass windows when looking up from the nave level. Luckily, the cathedral offers several tours, one of which affords visitors a chance to go behind the scenes, up stone stairwells, through back passageways, and view the windows up close. The closer I get to the windows, walking high above the nave on precariously narrow balconies, the more I am overwhelmed by their staggering detail.

As techniques changed throughout the years, the ways in which the windows were constructed changed as well. The earliest were made as they would have been in the Middle Ages—with painted glass joined by lead came. In 1937, church authorities dictated a new set of rules which resulted in windows made of richly colored glass. Themes explored in the intricate tableaus include biblical stories such as the Last Judgment, and less traditional scenes depicting military battles and scientific triumphs such as the moon landing. “There’s a lot of history in the windows—stories of the Bible but also of America,” Magner says.

The “Scientists and Technicians” window, designed by Rodney Windfield in 1973, features colors influenced by NASA photographs and includes a fingernail-size moon rock encased in a glass capsule. Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins graduated from St. Albans, one of the three schools associated with Washington National Cathedral.

The last window was installed in 2000, but some of the themes haven’t aged as well as others. In 2015, following a nationwide movement to remove Confederate monuments, the cathedral addressed its “Lee-Jackson” window, which featured Generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas Stonewall Jackson. The 64-year-old windows were eventually removed, with cathedral authorities saying in a statement: “The Chapter believes that these windows are not only inconsistent with our current mission to serve as a house of prayer for all people, but also a barrier to our important work on racial justice and racial reconciliation. Their association with racial oppression, human subjugation, and white supremacy does not belong in the sacred fabric of this Cathedral.”

Notable burials

Beneath Windfield’s window, I pay my respects to President Wilson and his wife Edith. Wilson was born just three days after Christmas, so it’s fitting that my view of his tomb is obscured by two women trying to make sense out of a large pile of evergreen branches. Following his death in 1924, Wilson was buried in the cathedral’s crypt, but he was moved up to the nave in 1956. Although Wilson is the only president interred here, the cathedral has hosted the funerals of four others—Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, Gerald Ford, and most recently, George H. W. Bush. On December 5, 2018, more than 4,000 people gathered for Bush’s funeral, a crowd that included five living U.S. presidents.

Washington National Cathedral is “a wonderful place for the country to come together in prayer,” Magner says. “It really pulls the country together.”

One floor beneath Wilson, the remains of two different but significant heroes are interred. Matthew Shepard was a gay University of Wyoming student whose savage death near Laramie in 1998 called attention to hate crimes and inspired legislative protections for the LGBTQ+ community. His remains were interred in the Chapel of St. Joseph of Arimathea in 2018, and in 2019, a memorial plaque was installed thanks to a grassroots, crowd-funded campaign.

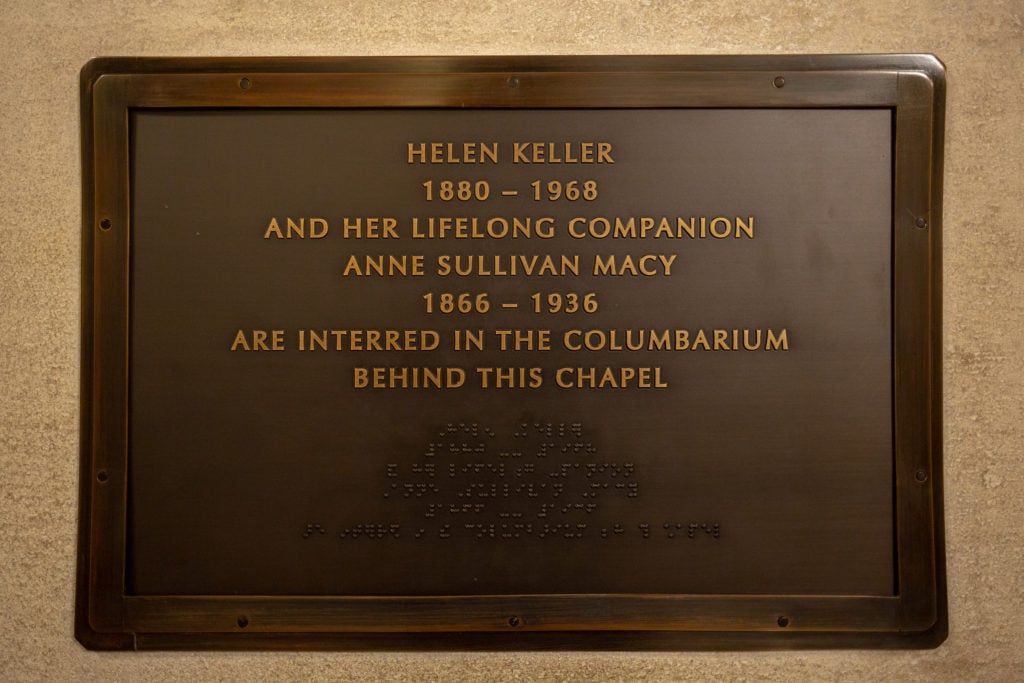

Interred near Shepard are the ashes of Helen Keller, author, lecturer, and disability activist, and her teacher and companion, Annie Sullivan. More than 200 other notable diplomats, congressmen, and members of the military are also buried at the cathedral. When I enter the underground chapel, located near the cathedral’s gift shop, to pay my respects, I have the solemn space to myself. But anyone is welcome to spend eternity here—for the right price. “If you have a million dollars, there’s room,” Magner says.

Gothic gargoyles

The Gothic-Revival cathedral is breathtaking in scope and scale, and that’s not an accident. “There is a wow factor,” Magner says. “[The architects] wanted people to be overwhelmed by the beauty because they built these things for God.” For many people, stepping inside of Washington National Cathedral—and other similar houses of worship around the world—is “as close to heaven as you’re ever going to get,” Magner says.

The central tower is 676 feet above sea level, making its top the highest point in Washington, D.C. Other buildings in the District may be technically taller, but the cathedral sits atop a 300-foot-high hill. “We have the higher ground,” Magner says. If there was some way to put the 555-foot-tall Washington Monument—D.C.’s tallest structure—into the nave, it would stick out the front door by just 25 feet. New York City’s Cathedral of Saint John the Divine is larger, but Magner points out that since its construction was never officially finished, Washington can lay claim to “the largest finished cathedral in the U.S.”

In 2011, two decades after stonemasons laid down their tools, an earthquake damaged both the Washington Monument and the nearby cathedral. Flying buttresses pulled away from the central structure, hand-carved angels and a 350-pound finial fell from the roof, and turrets shifted out of place. No one was hurt, but nearly a decade later, parts of the exterior are still clad in scaffolding, and restoration efforts are ongoing.

Initial construction on the cathedral cost $65 million, all of which was donor-funded, a model that continues today. “Everything in the cathedral is dedicated to somebody who paid for it,” Magner says. In the 1980s, a design-a-carving competition for children resulted in the Darth Vader grotesque, which was placed high upon the northwest tower. It’s difficult to see, but visitors wishing to catch a glimpse are encouraged to take a Gargoyle tour or bring binoculars.

Gargoyles and grotesques—the former assists with water drainage, the latter is more decorative—are another artistic element that’s difficult to appreciate without ascending toward the heavens. One gargoyle sports a conspicuous ring—its carver had just gotten engaged. “There’s a lot of whimsy,” Magner says. “Some of them are really fanciful. They reflect devils and lawyers. Some carvers made figures that resembled their girlfriends, their mothers, or, unfortunately, their ex-girlfriends.”

Heaven on Earth

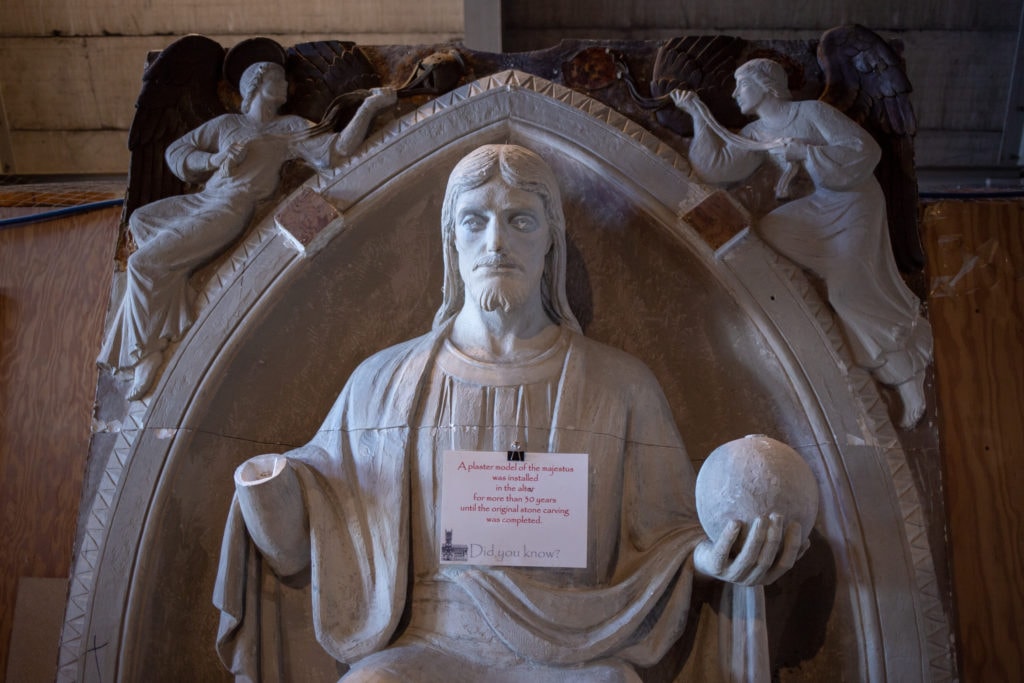

The cathedral currently employs three full-time stonemasons for restoration and repair work, but it’s difficult to find people with such specialized—some may argue antiquated—skills. But that wasn’t always the case. The central tower houses a dusty collection of dozens of champagne bottles representing five decades of New Year’s Eve celebrations by past stonemasons employed by the cathedral. The tower was closed for months following the earthquake, but it’s open now and, thankfully, the bottles managed to survive intact.

Houses of worship are often quiet places for reflection, but during my time spent exploring the grounds, one noise is notably absent: the sound of bells. The cathedral’s 64-ton Kibbey carillon is the third-heaviest in the world; it contains 53 bells weighing from 17 pounds to 12 tons. Above the carillon is a peal of 10 bells ranging from 608 pounds to 3,588 pounds. Volunteers and students ring the bells on Sundays, and during concerts and funerals, but most hours pass by silently. The silence is good for contemplation, but also for the cathedral’s relationship to the surrounding community. “The cathedral’s neighbors don’t like the bells,” Magner says.

Each week, the cathedral prays for one of the 50 U.S. states based on when it joined the Union. This includes the cathedral’s home of Washington, D.C., even if it has yet to gain statehood. “God knows the District of Columbia always needs prayer,” Magner says.

Over the course of my visit I use both the elevator and the stairs, but those wishing to climb 333 steps to the top of the central tower can participate in one of the cathedral’s tower climbs. I put in significantly less effort, but I’m still rewarded with spectacular 360-degree views of the surrounding area including the Potomac River, the Vice President’s residence, and the Washington Monument. From high atop the cathedral, D.C.’s tallest structure looks downright miniature. Whether or not you believe in a higher power or an afterlife, Magner is right: this may be as close to heaven as some of us get—at least in the District.

If you go

Washington National Cathedral is open Monday through Friday from 10 a.m to 5 p.m. and Saturdays from 10 a.m to 4 p.m. Sunday worship services begin at 8 a.m. and sightseeing tours take place between 12:45 and 5 p.m.