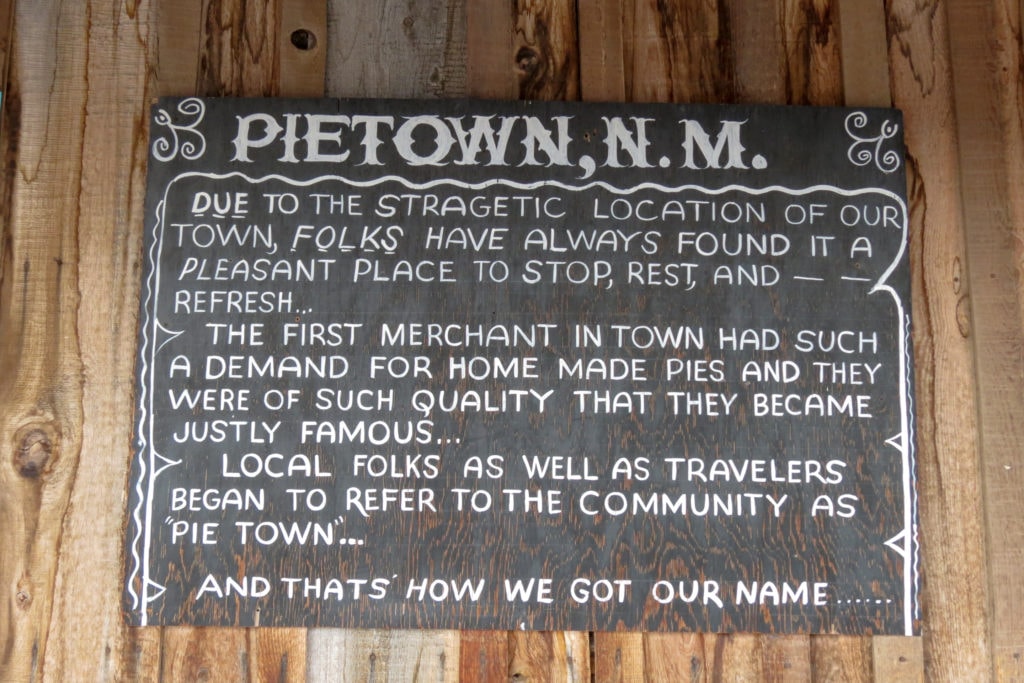

One of the joys of a road trip is passing by a town and wondering how it got its name. I've visited Why in Arizona, driven by Truth or Consequences in New Mexico, and one day I hope to pass through My Large Intestine in Texas and discover the delights of Intercourse in Pennsylvania. So when I found out that there was a Pie Town in New Mexico, I knew I had to go.

Pie Town is a 2.5-hour drive southwest of Albuquerque, close to the Continental Divide, and near the junction of Highways 60 and 603. Leaving I-25 behind at Socorro, I drive along Highway 60 as it climbs slowly but steadily upwards, heading for Arizona. Although I’m high above sea level—the elevation of Socorro is 4,600 feet and Pie Town is at least 3,000 feet higher—the landscape is barren and flat, with mountain ranges visible on the horizon.

After 30 minutes of desert scrub, with nothing but the occasional ranch in the distance, I see a few houses ahead and pass through the village of Magdalena, named after La Sierra de Magdalena (Magdalena Peak) which looks down over the village's few hundred people. The desert landscape is broken only by the surreal sight of several white satellite dishes, each the size of a single-story house, pointing up at the bright blue sky. I remember that this is New Mexico, home to Roswell, its International UFO Museum, and Spaceport America.

But my goals for this trip are slightly more down-to-earth. As the landscape becomes more scenic, the aptly-named Sawtooth Mountains rise to my right. Off to my left, trees are marking the start of the Gila National Forest. Straight ahead, a couple of miles past a sign for the Continental Divide, lies Pie Town. Desert has turned into dessert.

We serve pie

Blink and you might miss Pie Town altogether, if not for the large sign that reads “STOP” outside of the Pie-O-Neer restaurant. The sign is the work of Pie-O-Neer owner Kathy Knapp, and it works: I stop. Inside the cozy café, another sign says, "We serve pie. That's it."

The Pie-O-Neer’s mission remains true to the origins of Pie Town, which got its name in the 1920s when a baker set up a roadside stall selling New Mexico apple pies. He found that business was slow but steady, at first mostly through settlers heading west from places like Texas and Oklahoma. Places to stop were few and far between, so those homemade pies must have been a welcome sight.

Kathy Knapp first came to Pie Town in 1995 to help her mother make pies in the kitchen. "She was the baker," Knapp says. "I'd never made a pie in my life. I was a photographer, coming and going from Dallas, financing her dream. But then in 1997, when my mother couldn't stay at this elevation any longer, I became the baker by default. I called mom a lot, I cried a lot, and I threw a lot of pies away. But I learned."

A quick glance at the restaurant’s buffet-style pie bar shows that apple pies are still popular—and that Knapp obviously likes puns as much as she likes pies. The Pie-O-Neer offers flavors such as Peachy Keen, Starry Starry Blueberry Night, and Cheery Cherry. So what's her best-seller? "It depends,” Knapp says. “Probably cherry, overall, but coconut cream is the most popular with people of a certain age. Chocolate chess with red chile always sells out. We sell a lot of the New Mexico apple with green chiles and pine nuts too, perhaps because people are curious."

Complementary not competitive

Knapp says that according to the last census, Pie Town has a population of 187. "But where are they all—that's what I'd like to know,” she says. The zip code encompasses a 20-mile radius, including some large ranches which have been subdivided. Knapp says that people buy 20, 40, or more acres but not all stay, and attrition takes its toll. “In town proper, there's only a handful of families. And three places serve pies—two cafes and us."

The three pie shops—The Pie-O-Neer, The Gatherin’ Place, and Pie Town Cafe—try to be complementary rather than competitive. "Each place does their own thing, and then new seasons bring new owners or managers, and things change anyway,” she says. “And we all offer different styles of pie, which makes more people happy.”

The Pie-O-Neer is known for pies that aren't overly sweet and Knapp says they make an effort to substitute a flavoring, spice, or other ingredient in place of sugar. This does not work with eggy pies, though. “Chess pies, egg custards, flans, and so on all taste like wallpaper paste without enough sugar in them,” she says. “I can tell you that from experience."

Pi Day

In the summer, Knapp serves 20 to 30 pies a day and up to 50 if it's a holiday weekend. On the second Saturday in September, during Pie Town's annual Pie Festival, that number might be well over 250. But the biggest single day of the year aside from the festival is March 14—also known as “Pi Day”—when Knapp sells more than 80 pies.

I ask her what it's like to live in such a remote spot with only a handful of neighbors; moving from a big town like Dallas to tiny Pie Town could hardly be more of a contrast. The jokes and puns subside and Knapp becomes uncharacteristically pensive. "Well, Pie Town affords a peace that is not easily found, but nothing about it is easy,” she says. “It's isolated, and the elements can be harsh. If you're not good at entertaining yourself, then the quiet can be disquieting. I've actually left twice, defeated, but something kept drawing me back."

She pauses for a moment before the perky, pun-loving pie lady returns: "Maybe I just like the challenge of being a modern-day Pie-O-Neer."