Utah is a state known for its stunning national parks and eye-popping geology, but way down deep in southern Utah there is a place that stands out, even among these titans of natural beauty. It’s every bit as magical as its national park brethren and sistren to the north, but its trails aren’t strangled by tourists and its roads don’t have the constant drone of traffic.

Sounds great, right? Well, there’s a catch. Bears Ears National Monument—along with fellow stunner Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument—is looking at an uncertain future.

Bears Ears was first put on my radar in the summer of 2017, when the Department of the Interior announced that, by presidential decree, it was going to review the designations and protections for 27 of our national monuments. Essentially, the Trump administration wanted to undo the protections on these areas so that they could be sold to private interests, most commonly oil, gas, and mining industries.

As a big hiker and camper, wild places like these are my favorites to visit, so I wanted to try and do something to help. The DOI had an open comment period going, but it felt like this issue was going to get lost in the shuffle.

It occurred to me that I was sort of uniquely positioned to do something about it. I’m a journalist with my own photo and video gear, and I live in a van, which makes me extremely mobile. So, I set out in my van to visit all 22 land-based monuments that were under threat (the other five are way out in the ocean), in about as many days. I’d photograph them and make a one-minute video for each to raise awareness and drive people toward the government comment page. (You can check the project out at 27Monuments.org if you’re interested in knowing more.)

In the end, the government received more than 2.7 million comments, more than any previous call for comments. They then promptly ignored them. First to the chopping block would be Bears Ears National Monument in Utah. In 2017, President Trump controversially reduced the size of the monument by 85 percent. This led to a slew of lawsuits fighting the decision, including one by the outdoor brand Patagonia.

But there’s hope. Just last week, the Senate passed the Natural Resources Management Act, which protects millions of acres of public land. Also this month, the Democratic-led House introduced legislation to not only restore Bears Ears to its original size, but to expand it even further.

So, this is a story about Bears Ears. Why it’s important, why you should visit, and why it should be protected.

What is this place?

Bears Ears National Monument was originally designated in late 2016, at the very end of the Obama administration, at 1.35 million acres. Five local Native American tribes have strong ancestral roots in the area and worked together in an unprecedented way for many years in order for it to get protection under the American Antiquities Act.

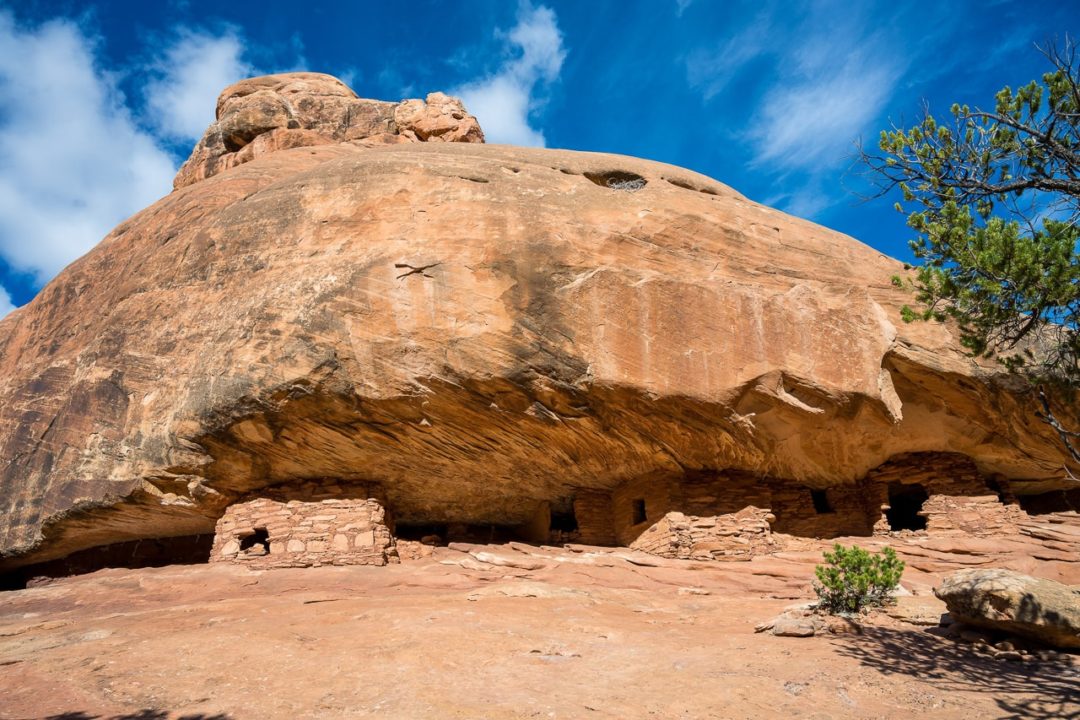

Bears Ears boasts incredible rock formations, sweeping views, and incredibly well-preserved Native American artifacts, ancient cliff dwellings, and petroglyphs—not to mention countless sites teeming with fossils.

National monuments in the wild are different from national parks, where everything is paved and campgrounds fill up a year in advance. These places tend to be rugged. There aren’t as many rangers, the roads are often dirt and not as regularly maintained, and most sites have no services. Even finding a decent map can be difficult.

The reward is that these are places of incredible freedom. You can camp in them, often for free, practically anywhere you want. You may not see or hear another car all day, depending on where you go. They are public lands renowned for their hunting, fishing, and hiking.

When I was doing my monuments trip, Bears Ears was my fourth stop, but it was the first one where the gravity of the situation really hit me. Driving into it, you’re immediately struck by its majesty. It’s massive, and it’s breathtakingly beautiful. Everywhere you go, the history radiates back at you. All around you are signs of humans who lived here many thousands of years ago.

This ancestral land is such an important part of the human story, and it’s one we’ve really only just begun to explore.

Our favorite spots to visit

Valley of the Gods

This is one of those rare places that makes you feel like you’re on an alien planet. The “Gods” in this context are dozens upon dozens of massive sandstone rock formations. They are intricately layered buttes and monoliths that rise hundreds of feet high. Valley of the Gods is just a quarter of the size of the nearby Monument Valley, but it’s no less spectacular—and I’d wager you’ll encounter at lot fewer tourists.

A 17-mile road that loops through the Valley of the Gods affords incredible access to these natural mega-statues. The road is dirt and gravel, but it’s fairly well-maintained, and a normal two-wheel drive car shouldn’t have a problem with it when it’s dry—though it does cross a couple of washes. When it’s been raining, it’s probably not safe even with a 4×4. If you’re planning a visit, call the local BLM office to get info about road conditions.

When the weather is good, you’re in for a serious treat. When I drove through in mid-October, there were tons of open, large campsites, just in the shadows of some of the most picturesque monoliths. No reservations are required in this area, and it’s totally free. I’d recommend entering from route 163, just north of Mexican Hat, Utah.

Wolfman Petroglyph Panel and Small Ruins

When I came upon the Wolfman Panel in Bears Ears it was the first time that it hit me just how sacred this place is. I had never seen petroglyphs this distinctive and (almost) perfectly preserved. Ancient Native American hands used sharp rocks to “peck” these intricate, detailed images into the rocks, and when you stand there, you can feel that history deeply embedded in the place.

The trailhead is a pretty short drive from Bluff, Utah, located on the incredible Butler Wash. Lower Butler Wash Road (Country Road 262) is just about five miles from Bluff, and once you get off the highway (opening and then closing a gate behind you), it gets pretty rugged. High clearance vehicles are generally recommended, especially if you’re going further into the wash, but the trailhead for Wolfman Panel/Small Ruins is only about a mile in and a two-wheel drive car should be okay if the conditions are good. For the most detailed driving and hiking directions, I would refer you to this page, which includes GPS coordinates for the trailhead, and a solid description of the trail itself. Save that page on your phone (or print it out), because you will almost certainly have zero reception out there.

The hike itself is short, but I’d call it somewhat strenuous, because you need to squeeze through a couple of tight cracks and do a bit of scrambling. Again, I’d recommend following the trail description linked above and/or this one, because the trail is not well marked in many places and I lost it a couple of times on my way down. You’ll find the Wolfman Panel on your left as you work your way down into the canyon (it’s about 0.4 miles from the trailhead, though it’s an out-and-back, so plan accordingly). Take it in, but don’t touch, as the oil from your fingers can discolor these relics.

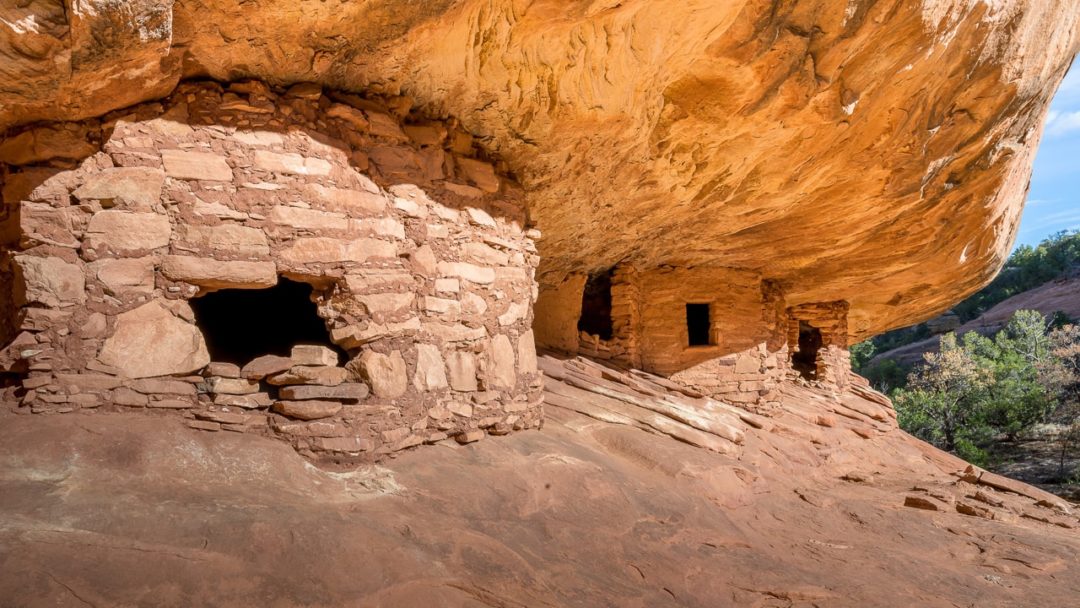

Speaking of relics: If you’ve got a little more juice in you, keep following that trail down into the wash. Just another 0.3 miles in, you’ll cross the wash and be rewarded with Small Ruins, a set of incredible dwellings at the base of the cliff. Please don’t touch them because they’re fairly fragile, but if you’re careful you can actually stick your head in there and look around inside. I found it to be a very powerful experience.

You can camp just about anywhere on Butler Wash, and you’ll really feel like you’re out in the middle of nowhere.

House on Fire

House on Fire is one of the best-preserved Ancient Puebloan ruins in the area. The colorful and uneven texture in the cliff just above these ruins makes it look like massive flames are pouring out of the roof. This effect is especially exaggerated in late morning when the light reflects off the opposite side of the canyon. I was there in the early afternoon and it was still stunning. Despite it being a well-worn trail, you really feel like you’re in the wilderness here. This is emphasized when you get a strong whiff of juniper trees, which are prevalent throughout. It’s also not far from the aforementioned Butler Wash sites, so if you start early, you could easily hit both in a day—again, provided your vehicle is up for it.

The hike to the House on Fire ruins is just a moderate, three-mile out and back round trip. If you’re up for a longer adventure, though, there are another eight or so ancient cliff dwellings further into the canyon, along with some rock art. Some of them are very high up on the cliff walls and may be easy to miss.

House on Fire itself is a popular attraction (especially in the late morning), and the roads leading to it are generally pretty well-maintained. It should be fairly accessible year-round, though if there have been heavy rains recently, I’d think twice. It’s always a good idea to call the BLM office to hear about road conditions before you commit.

Good to know before you go

Southern Utah tends to be a hot, dry place, especially during summer months. Having a good system for carrying plenty of water is absolutely essential. The BLM recommends carrying a gallon of water per person, per day. Dehydration and heat stroke are some of the biggest hazards here. Check the weather before you go, and consider being off the trails for the hottest part of the day. But heat isn’t the only danger; these areas are prone to flash-flooding, and this is especially dangerous if you’re hiking into a wash or canyon. Again, check the weather just before you go, and make sure there’s no rain coming to nearby areas that could unload there.

Another recurring theme is knowing the road conditions before you head out. Many roads here are prone to turning into a very slippery soup when soaked. Gas stations are few and very far between, and I’d definitely recommend carrying a gas can. Also bring a spare tire, and, again, plenty of water and food in case of emergency. Make sure you call the BLM Monticello Field Office at 435-587-1500 to get info about road conditions.

Speaking of calling, there is very little reception in these places, and that means your phone isn’t going to be good for much unless you plan ahead. Download maps and trail descriptions to your phone before you go off the grid.

For more info on Bears Ears National Monument, as well as more safety info, take a look at its BLM page.