When a 5,000-pound totem pole embarked on a 2-week, cross-country road trip in mid-July, it didn’t pack light. The 25-foot-tall sacred object traveled from Washington state to Washington, D.C., on a flatbed truck—accompanied by a caravan of cars, its own security force, and thousands of prayers and blessings from all of the people who met it along the way.

“Every single person that touched it—a little piece of them is with that pole,” says Wolf, one of only two members of the Ti’Tuwan Security Force to travel with the pole from start to finish. “There’s no way not to feel something when you come around it.”

The 400-year-old red cedar tree began its journey, dubbed the “Red Road to D.C.,” from the Lummi Nation near the Salish Sea on July 14. It traveled more than 20,000 miles, to eight different sacred sites around the country—Snake River, Bears Ears National Monument, Chaco Canyon, the Black Hills, Missouri River, Standing Rock, White Earth, Minnesota, and Mackinaw City, Michigan—before arriving at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) on the evening of July 28.

The next day, a welcome ceremony held nearby on the National Mall drew a sizable crowd of supporters and speakers, including Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary. After the event, the pole was moved to Rawlins Park (outside of the Haaland-run Department of the Interior) for the next few weeks while organizers search for a more permanent home.

“Native people are on the rise,” says Wolf. “We’re starting to get back on our feet, we’re starting to get through that generational trauma—you never get over it but you can deal with it, understand it, and learn from it. This totem pole was the perfect statement of our presence—we plan on being heard from here on out. Leaving that here with all the prayers that came with it is kind of like saying, ‘You’ll remember that we were here.’”

Piscataway land

Just after 2 p.m. on July 29, the totem pole ceremony begins like almost every socially-conscious event near the Capitol—by acknowledging that no matter where you go in the U.S., “here” is technically stolen land. Although it feels like it on a hot and humid day like today, Washington, D.C., was not actually built on a former swamp. But long before the politicians arrived, the Piscataway people called the area along the Potomac and Anacostia rivers home. And they still do: In 2012, two groups representing Piscataway descendants received recognition by the state of Maryland as Native American tribes (they are not yet federally recognized).

The crowd includes several different Tribal Nations who have traveled to D.C. to welcome the pole. They hope their presence will urge legislators to “recognize the political standing and equality of Tribal Nations to be at the table and heard in good-faith government-to-government negotiations,” says Fawn Sharp, president of the National Congress of American Indians.

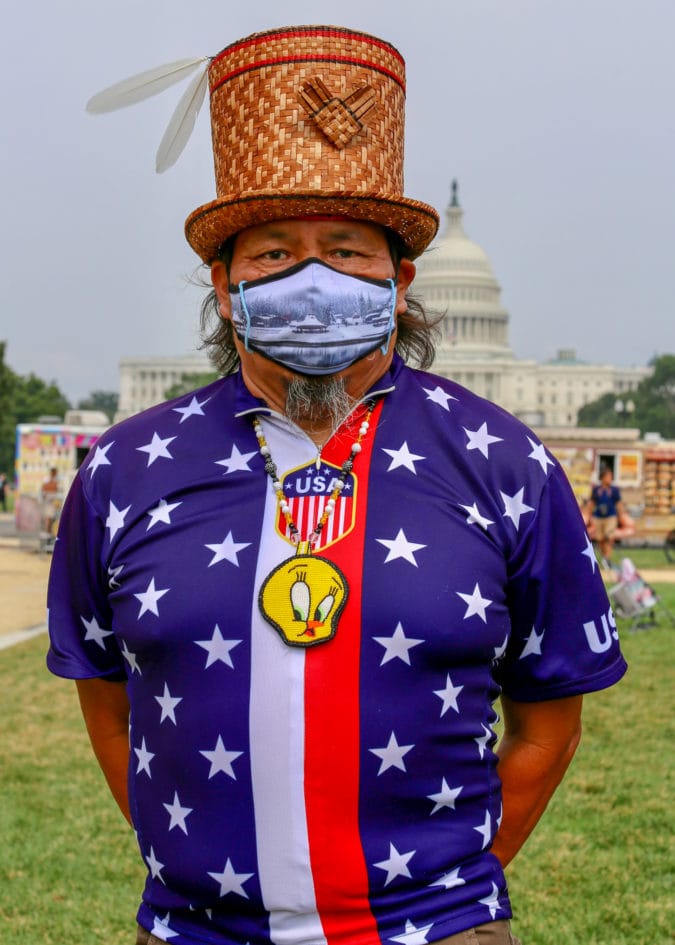

The crowd is dressed in long colorful skirts, embroidered vests, headdresses (featuring both flora and fauna), and hats. One man wears a beaded medallion shaped like Tweety Bird; in another, a swan emerges from a patchwork of dyed porcupine quills. People (including Haaland) line up to touch the totem—it’s not only allowed, but encouraged—and leave offerings; a man lights a sage smudge stick and waves it over the pole.

Wolf says as a Michigander, he’s used to the muggy East Coast summer. But during the journey, he fell in love with the West Coast, the dry heat of the Utah desert, and the otherworldly beauty of South Dakota’s Badlands. “It was fascinating to go up through Lummi country,” Wolf says. “Those views are just breathtaking—even with the haze from the forest fires. It’s also very easy to die in the Badlands—it’s one of the best-looking places in the country and it’s just man-eating.”

Death and destruction

“Man-eating” could also describe this busy, hot summer on Capitol Hill. The House of Tears Carvers of the Lummi Nation created the pole specifically for the Biden administration; not necessarily as a peace offering, but more of a “welcome to the neighborhood” gift basket (with conditions). Carved and painted in just three months, the pole was sent on its cross-country tour to highlight several sacred Indigenous sites currently at risk from infrastructure and resource extraction projects such as pipelines, coal ports, and offshore drilling.

The caravan traveled to North Dakota’s Standing Rock Reservation, where camps sprang up in 2016 to protest the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Native organizations and climate activist groups continue to fight similar projects that threaten to disturb sacred sites and pollute crucial water sources, such as Minnesota’s Line 3 and West Virginia’s Mountain Valley pipelines.

House of Tears master carver Jewell James wasn’t able to travel with the pole due to health issues, but in a video currently on view at NMAI, he says: “We know the public is tired of seeing the same thing over and over—death and destruction. We like to use a totem pole to kind of awaken something inside them—to come together and look at the science and look at the facts and make a decision to protect the air, the water, and the land and the health of the people.”

Enough is enough

The House of Tears has sent more than a dozen totem poles on journeys for various causes, including one honoring 9/11 Pentagon victims that stands in Congressional Cemetery 2 miles east of the Mall. The Red Road to D.C. totem is twice as tall and intricately carved with symbols from the natural world. A bald eagle head juts out from the top, a man prays, and a girl kneels near a grandmother; hammered copper accents glint in the midday sun.

James says that the inspiration for the pole was borne of frustration: “We say Kwel’ Hoy or ‘Enough is enough.’ We’re killing off all the cultures that protect the earth, reinforcing the cultures that destroy the earth, and, as a consequence, creating a world our children can’t live in.”

Wolf has been with the Ti’Tuwan Security Force since 2016. Horrified by the graphic footage of private security guards unleashing dogs on protestors, he says he drove to South Dakota and joined the Standing Rock camp for 5 months. The “Lakota brotherhood” is tapped for treaty meetings and sun dances or just to keep the streets safe at night; they distribute food to their community and help out wherever, and for however long, they’re needed.

Wolf can’t stay in D.C. too long because he’s organizing an event back home in memory of his sister, who was murdered in November 2020. Several red handprints on the top of the pole represent the hundreds of Indigenous women who are murdered or go missing each year. “Somebody has to stand up and say, ‘No more.’” says James. “We need to lock arms. We need to join hands. It’s everybody’s battle, every child—whether they’re red, black, white, or yellow. All of us have to draw the line and unify.”

A plethora of emotions

Although the totem pole arrived at NMAI—and was parked outside the museum’s Maryland Avenue entrance for a few days—engineers say it’s too heavy to be moved inside. Until September, the exhibition Kwel’ Hoy: We Draw the Line is on display in the lobby, featuring objects curated by communities that welcomed another traveling totem in 2017. A decal of the Red Road pole is affixed to one of the building’s curved columns in lieu of the real thing.

Wolf says he’s glad this particular pole didn’t end up in the museum. “I think it’s important that we divide it up,” Wolf says. “The museum already makes people feel a plethora of emotions—this totem [will be] a new place for people. They won’t even have to understand what it is they are feeling, if it makes them open up a little bit and want to look into it. I’m happy that it will be visible, that people can learn those lessons, and that they can feel it.”

No matter where the totem pole ends up, it can thank Wolf—and dozens of other Native organizers, artists, and activists—for getting it there safely. Luckily, the group faced few obstacles beyond normal road fatigue. After 2 weeks of near-constant travel and vigilance, Wolf admits he’s tired: “It wears on you, the level of dedication. We took oaths to do this kind of thing and we hold those very sacred.”

Wolf was always confident in his team’s ability to keep the pole safe from potential vandals—or on hairpin turns after a misunderstanding took the caravan through Colorado’s precarious Wolf Creek Pass. But he says he was surprised at the pole’s unanimously warm reception; no matter where they were, he says that people would run up and take photos—even if they weren’t all aware of the object’s provenance, significance, or final destination.

“Most people don’t understand what this pole represents, they just find it fascinating,” Wolf says. “Most Americans love Indians as long as we’re old Indians—if we start bringing up the traumas we’ve been through, suddenly they don’t like Indians anymore. But it didn’t matter where we were—or the racial temperature of the area—they just all loved it.”

If you go

The totem pole will be on display outside of the U.S. Department of the Interior in Rawlins Park until a more permanent home is found.