Highways, freeways, parkways, whatever you want to call them, they all look and sound the same these days—multi-lane gray portals dotted with large green overhead signs. However, there is one particular road that stands apart, slower and more colorful than all the others…

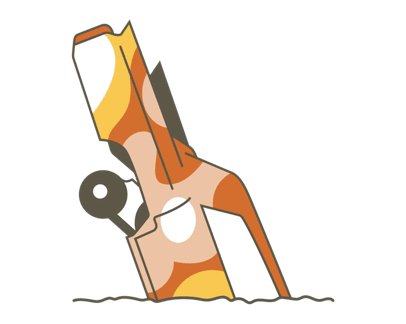

In contrast with today’s fast-paced, globally-connected world, Route 66—which required motorists to slow down through every little town along its path—positively plodded. That’s why it’s worth taking a closer look at this now-popular feature of the American landscape. It offers the unhurried wayfarer a chance to sift through the ever-crumbling layers of past and present to better understand the talent for roadside promotion that has always characterized what is, essentially, a nation of entrepreneurs. Its place in the history of American progress, and the folklore surrounding it, has brought the famed Chicago-to-Los Angeles route to global attention.

Having made nearly two dozen cross-country road trips myself, Route 66 was one I’d never tackled, save a few snippets of it here and there in Arizona and New Mexico. So I did the whole thing, in a broad sweep (with the occasional rest at a Comfort Inn) from the Old Northwest to America’s finish line—the shining jewel that has motivated so many people to pack up and head toward the setting sun in search of a better life.

Get your kicks

Following Route 66 in modern times can be a little complicated. In some places, brown “Historic Route 66” signs have been posted to direct motorists along sections of the historic highway that haven’t been subsumed by the interstate. In others, the trail fizzles out. Even so, there are times where the tourist traveler has no choice but to face modernity square in the face and merge onto a high-speed, limited access highway. But, armed with the right maps and guidebooks, it’s possible to piece together much of the non-interstate route, as it winds through some of the most beautiful towns and landscapes to be found anywhere in the western two thirds of the U.S.

There’s a lot to see, more than enough to fill a book. So I’ve collected a few highlights from my trip to give you an idea what’s out there.

Illinois

Illinois

Taking in the deep blue of Lake Michigan at the eastern terminus of Route 66, I climbed into the car and pointed it west on E Jackson Drive. By the time I reached Dell Rhea’s Chicken Basket—a classic Route 66 restaurant that has been in operation just outside Joliet since the ’40s —66 had fizzled into a semaphore of feeder roads next to I-55. The restaurant was still there, and was packed with diners. An elderly lady and her husband emerged from the restaurant to get in their car and go home, and she told me she had gone to Dell Rhea’s after her prom in 1952.

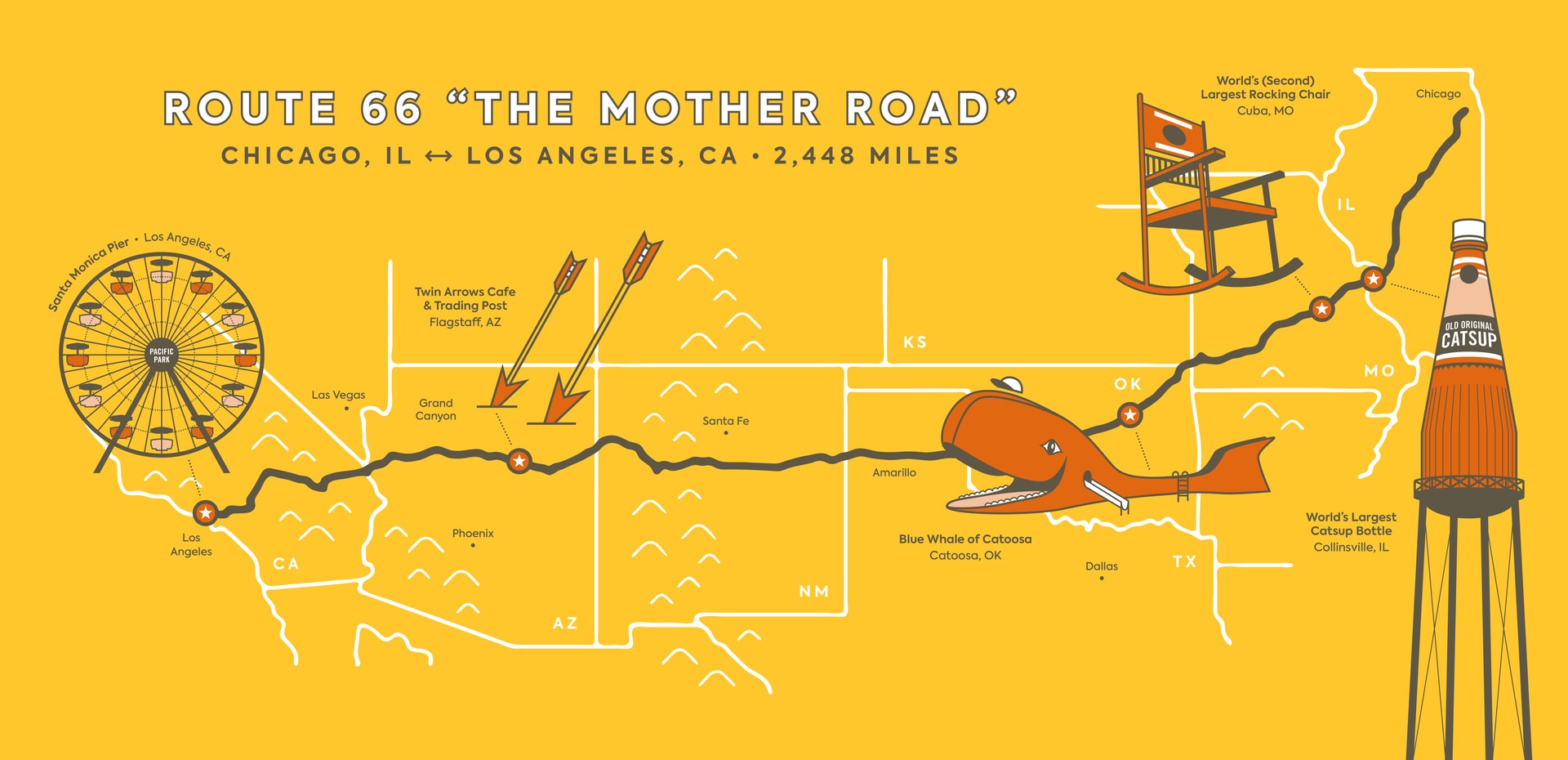

Outside of Chicago, Illinois is farm country. The summertime scenery alongside 66 is green and lush, and like everywhere along the route, people have put old, rotting cars on display as an homage to the highway’s storied past. But as the countryside morphs into faded suburbs, the last big roadside attraction along 66 is the world’s largest catsup bottle. It’s actually a water tower, built in 1949 to supply the adjacent catsup plant.

The Brooks Catsup plant is no longer in operation, but local volunteers raised money to have the tower restored in the early ’90s. It has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 2002.

Missouri

Missouri

After crossing the Mississippi River into St. Louis on the 109-year-old McKinley Bridge, I made my way down various snippets of the route (even passing the world’s second largest rocking chair) until I arrived at the Jesse James Wax Museum. If the founder of this museum, Rudy Turilli, is to be believed, you may as well forget everything you know about Jesse James.

The $9 museum tour begins with a 15-minute film detailing James’ past as a pro-Confederate guerilla and, later, a bank, stagecoach, and train robber, before it launches into an alternate ending of the familiar James Gang tale. The museum claims that James didn’t actually die in 1882, but rather much later in 1951. And that the man who did die in 1882 was someone by the name of J. Frank Dalton. Photos aren’t allowed in the museum, so you’ll just have to (fondly) remember the lanky wax figures in their suits and ties.

Moving southwest from the museum, Route 66 takes longer swoops away from I-44, offering a scenic path through the Ozarks toward Springfield and beyond. I was told by various people in southwest Missouri to go see Red Oak II—a cluster of old houses sitting in the middle of otherwise empty farmland a few miles outside Carthage. There was a diner, a schoolhouse, some houses, a church, and a gas station or two, along with a bunch of old cars rusting quietly here and there. As instructed, I began scanning front porches for Lowell Davis, the sculptor who had created the town. I found him sitting in a chair on one of the porches, smoking a corn cob pipe. Sporting a checked newsboy cap atop a Twain-esque mane of silver hair, he invited me to sit on the porch with him.

Davis explained that Red Oak—the original one, where his family was from—had been a small rural town about 20 miles away. After World War II, when people began moving to larger cities and towns in search of greater prosperity, Red Oak began its inexorable decline. Davis, who had a successful career sculpting figurines for companies that distributed them to gift shops, didn’t want to see the town disappear. So he started buying up farmland outside of Carthage and snapping up vacant buildings in Red Oak. After moving the buildings to the farm, he had a blank canvas upon which to create his own interpretation of Red Oak, complete with a pond and a cemetery.

Kansas

Kansas

After leaving Red Oak, my run through Kansas was short but sweet. Route 66 only runs 13.2 miles through Kansas—plunging in, making a sharp left past some old trucks dressed up to look like characters from the Pixar film Cars, then beelining toward Oklahoma. It’s easy to see why the interstate bypassed the string of mining towns that pepper the state—it’s neither convenient nor scenic.

However, I still found beauty in the Rainbow Bridge just north of the Oklahoma border. The bridge, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, no longer carries through traffic, but you can still drive across it. See if you can spot the almost-faded Kansas Route 66 sign at the start—a subtle reminder of the bridge’s glory days.

Oklahoma

Oklahoma

According to most sources, the idea for Route 66 originated in Oklahoma. Cyrus Avery—a Tulsa oilman and cattle rancher who got involved in the Good Roads Movement, and later the federal commission that created a numbered highway system in the U.S.—was instrumental in making sure 66 passed through his home state. Avery’s early 20th century scheming may have had a chamber of commerce bent, but the resulting route had an unintended side effect—it helped millions of people escape the economic devastation brought on by the Dust Bowl during the 1930s. But more on that in a bit.

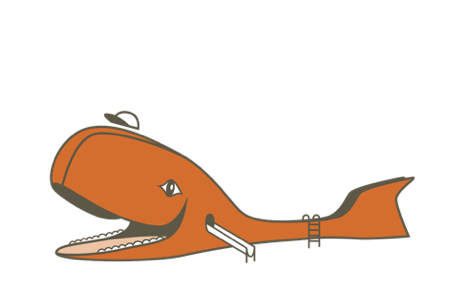

After bypassing both the whimsical Blue Whale of Catoosa and the Hole in the Wall Conoco Station—the latter being located just a few blocks from where baseball legend Mickey Mantle grew up—I pressed on to see some dazzling modern murals that had absolutely nothing to do with vintage ads or the old way of life. Sponsored by the Oklahoma Arts Council, these works showed off the creativity that is still very much alive outside of places like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

-

Allen’s Conoco Fillin’ Station. | Photo: Benjamin Preston -

Miami, Okla. (pronouced My-am-uh) is home to a number of stunning modern murals.

| Photo: Benjamin Preston -

An abandoned farmstead near Sayre. | Photo: Benjamin Preston -

Waylan’s Hamburgers. | Photo: Benjamin Preston

The Oklahoma Route 66 Museum in Clinton was one of the stops most poignant to the overall route. The museum is organized into a series of rooms dedicated to each decade of the highway’s life. It can be boiled down to this: Construction in the ‘20s; Dust Bowl flight in the ‘30s; World War II military travel in the ‘40s; vacation in the ‘50s; decline from the ‘60s on.

Headed west from Texola into the eastern part of the Texas panhandle, large swaths of the original sectioned Portland concrete roadway are still extant. Slowing down to 50 miles per hour, I listened to the steady “pock-pock, haahsssssss, pock-pock, haahssssss” as the tires rolled over the sunbaked slabs. I imagined I was a ‘50s vacationer, headed west to California in a modest Pontiac sedan. Then I pushed the speed higher, and higher still, listening to the more staccato rhythm Clark Gable would have heard as he piloted his ’49 Jaguar XK 120 across open country, far from Hollywood’s raucous clamor.

Texas

Texas

Despite its oft-repeated claims of being the biggest and best at everything, Texas has jurisdiction over the second-shortest length of Route 66. Headed west, Shamrock is the first town you encounter after leaving Oklahoma. It’s a quiet town, but the late-’30s vintage art deco U-Drop Inn is one of the most gorgeous structures to be seen on the entire route. A beautifully restored Magnolia filling station and the Pioneer West Museum are just around the corner. Shamrock also boasts a plaza with a kissable chunk of the actual Blarney Stone.

I stopped for dinner at the Big Texan Steak Ranch in Amarillo, but didn’t opt for the “free” 72-oz. steak (you only get your meal gratis if you finish your four-and-a-half-pound steak, a baked potato, a side salad, a shrimp cocktail, and a buttered roll in less than an hour) but still managed to enjoy a Texas-sized dinner. There was a Comfort Inn & Suites a few minutes down the road—a godsend after a huge meal.

The famous Cadillac Ranch sculpture juts out of a field just west of town. It had rained, so the place was a mudhole, but that didn’t stop visitors from squelching into the muck to leave their mark on the battered cars. By lunchtime, I had reached Adrian, Texas, which is 1,139 miles from both Chicago and Los Angeles. I was already halfway there.

New Mexico

New Mexico

Not quite 50 miles west of Albuquerque, Route 66 splits away from I-40, snaking through a series of villages with predominantly Native American populations. Acoma Pueblo sits atop a tall mesa a few miles south of 66. It has been continuously occupied by the Acoma people for more than 2,000 years. Today, the tribe sells traditional ceramics and jewelry, and operate the Sky City casino, which is located next to I-40.

Unlike Missouri, where points of interest are so closely packed, New Mexico’s offerings are much more widespread in the open desert. But the craggy red-brown landscape and a deep blue sky filled with fluffy clouds makes it all worth it. As the state’s license plate says, New Mexico really is a land of enchantment.

Arizona

Arizona

Even with so many things to see in Arizona, its biggest attraction is the Grand Canyon. The canyon’s south rim is more than 50 miles from Route 66—snaking through the frigid mountain town of Flagstaff and bypassing the famous Twin Arrows—but a 100-mile round trip is nothing when you consider the grandeur of this natural marvel. I know this sounds cliché, but words cannot describe how breathtaking a spectacle it is. I had seen Copper Canyon in Mexico—which is bigger—but the Grand Canyon’s red rock sets it apart in terms of sheer beauty.

After gawking at the canyon from various angles on the south rim, I drove back down to Williams, Arizona, where I spent the night at a Comfort Inn conveniently located near the region’s attractions.

Route 66 wanders away from I-40 again west of Ash Fork. In Seligman, I stopped at Delgadillo’s Snow Cap Drive-In, which is best described as an ice cream and hot dog shop that plays practical jokes on people.

As soon as I saw the neon “Sorry, We’re Open” sign, and the Christmas tree-adorned ’36 Chevy sitting next to it, I knew something was up. I didn’t realize to what extent until I went to pull on the doorknob beneath the “pull” sign on the door to the ordering counter, only to realize that the actual knob was on the other side of the door. When I announced to the lady behind the counter that I’d been had, she said, “But now you’ve been had by mustard!” and aimed a big squirt bottle at the center of my chest. Thankfully it was filled with yellow string. Juan Delgadillo opened the Snow Cap in 1953, and although he passed away in 2004, his daughter Cecilia (the one with the fake mustard bottle) and son John carry on his traditions.

California

California

I can’t imagine what Okie migrants fleeing Dust Bowl privation must have thought when they crossed the Colorado River and beheld that first “Welcome to California” sign standing in the middle of the Mohave Desert. Needles, the first town they would have encountered, is one of the hottest places in America, if not the world. Temperatures often soar well above 100 there, as they did when I arrived (the car’s outside temperature gauge said 103 degrees Fahrenheit).

But the sun went down and the roof came off. That’s the beauty of the desert once the sun disappears for the night—the air cools to a comfortable, sometimes even chilly, temperature. The only reminder of the day’s scorching heat came when I drove beneath overpasses, and the warmth stored in the concrete slabs radiated down into the car. It was moments like these, where the overpass cloaked me in a flash of hot air, that I realized my four-wheeled odyssey was coming to an end.

From Needles, a great distance must be traveled before the California climate becomes temperate again. I cut a straight path toward the cool breeze blowing off the Pacific Ocean, arriving just in time to take in a delicious sunset at the end of the Santa Monica pier. This was what all the fuss was about—the reason for the 2,448-mile drive. Like so many before me, I leaned back in my chair and exhaled. I’d made it.

As they stand and face the harshness of several different climates, the remains of Route 66—and its surrounding oddities —face their greatest challenge to date: the ravage of time. And while nothing lasts forever, the American idealism that seems to permeate every diner, hotel, and mile marker along Route 66 is what continues to capture everyone’s attention (myself included). For I believe, as long as it’s possible to hop in a car and head for the coast, the Mother Road will stay alive.

Illinois

Illinois Missouri

Missouri Oklahoma

Oklahoma

Texas

Texas New Mexico

New Mexico  Arizona

Arizona California

California