A collection of unlikely characters is standing around a fire in the middle of the California desert. There’s an older woman who introduces herself only as Tomahawk, kindly offering to give away a handful of colorful gems she bartered at a recent “trade circle.” Next to her is a bearded man—a former banker, he says—who’s currently staying at the rag-tag community’s hostel for the season.

A pregnant woman is sitting in a cracked lawn chair, talking emphatically about tonight’s meteor shower, and a quiet young couple have their arms around each other. Every half an hour or so, like clockwork, the makeup of the group around the fire changes, filtering in newcomers from different corners of the decades-old camp known as Slab City.

The isolated desert community was created by transient, freedom-seeking people like these, all living off the grid in trailers, tents, lean-tos, and broken-down school buses in a remote patch of the Sonoran Desert, on the eastern shore of the Salton Sea.

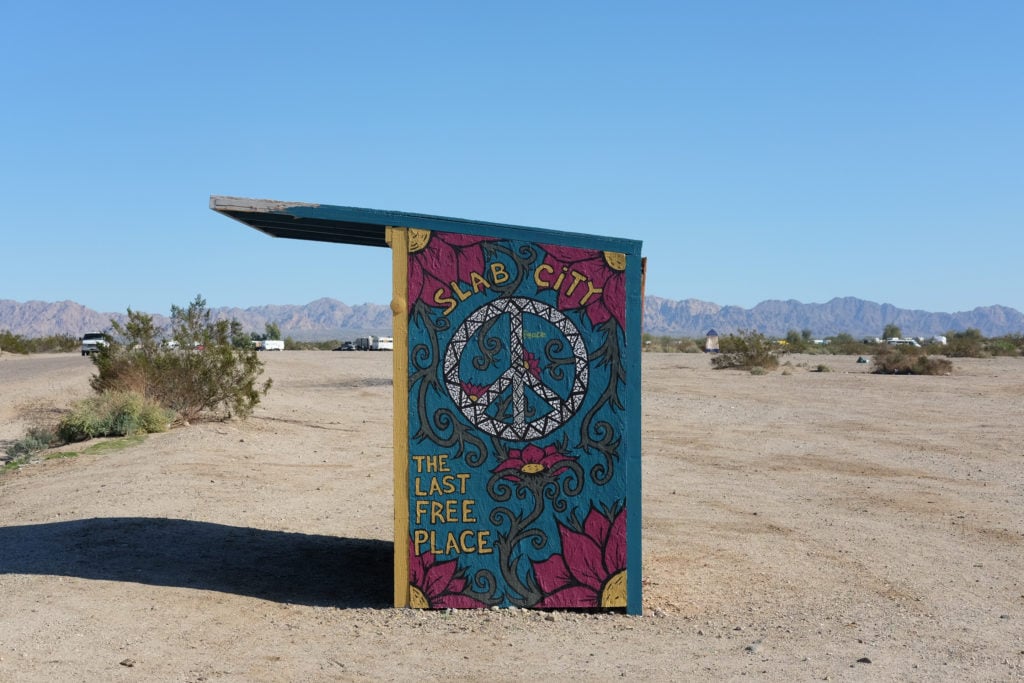

The last free place

Here, the word “city” is a bit of a misnomer. The Slabs, as the community is known, has no connection to the main power grid, no trash or water services, and a general lack of basic amenities. The encampment is as bare bones as it gets. Streets are made of hardened dirt, most structures are built from salvaged materials, and packs of dogs roam the area.

But despite its wild appearance, Slab City has undergone a significant transformation in the last few years. Now its population swells to a few thousand people in the winter months and roughly 150 in the summer, when temperatures can soar up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit and leave desert dwellers particularly vulnerable. But with a bigger population comes real city problems: theft, drug abuse, an influx of trash, and the challenge of successfully starting community programs.

The camp’s tagline may be “the last free place,” but as Tomahawk says while she wrangles an armful of brush into the fire: “Freedom isn’t always free.”

The Slabs has long been a destination for nomadic-minded people from around the country. The encampment was first formed after a military training facility in the same location, Camp Dunlap, was dismantled in the 1950s. Soon after, drifters started trickling in, setting up their own camps and naming the area after the concrete slabs left behind from the base. The land is owned by the state of California, technically making those who live here squatters.

Today, the remote community has adopted some elements of a bona fide city. The streets are named, there’s a small library, a few establishments sell food, and several places are available to rent on Airbnb. Located at the entrance of the Slabs, Salvation Mountain—a technicolor art project created by local artist Leonard Knight—also brings in dozens of camera-wielding tourists a day, though most don’t venture past that point.

Download the mobile app to plan on the go.

Share and plan trips with friends while discovering millions of places along your route.

Get the AppCalifornia Ponderosa

Slab City has more than a dozen individual neighborhoods within its limits. Each neighborhood consists of a small camp of people with their own particular rules and culture.

One such group on the edge of town is called California Ponderosa, led by a man with a wispy white beard who introduces himself as Spyder (Slab nicknames are earned, Spyder explains). The nucleus of Ponderosa is a makeshift kitchen/bar/outdoor living room, made out of plywood, sheet metal, wooden pallets, tarps, and a whole host of other found materials.

This time of year, during the Slabs’ busy season, Spyder has 12 people staying in his camp, plus his wife and kids. He charges each person $125 a month in exchange for daily breakfasts and dinners. Ponderosa also boasts its own outhouse and an outdoor shower facility. Other camps in the Slabs operate under a similar premise—snowbirds pay a monthly fee for certain “amenities.”

“It’s been one of my big dreams to have a place to serve food, make people happy, make a relaxing atmosphere,” Spyder says, sitting behind his bar after a recent morning breakfast rush.

Spyder first moved to the Slabs nine years ago. Though he didn’t initially intend to stay, he had three kids in tow and vehicle troubles, so he sold his truck and set up a campsite across the street from Ponderosa. Eventually he bought out the original owner of several nearby structures and started running his own business.

“Every year I learned something new because [living] out here is really rough,” he says. Luckily, Spyder’s past work experience in the outside world, from carpentry to plumbing to working in the restaurant industry, made for conveniently transferable skills. “I take everything that I’ve learned and bring it out here,” he says.

“If you go to New York, Boston, San Diego, wherever, you have these types of people there in the cities, too. You just choose to ignore them.”

Aside from the pure logistics of setting up camp in Slab City, there are personal dynamics to contend with, too. As Spyder explains it, Slab City encompasses a wide spectrum of humanity in one small desert plot, including addicts, former convicts, and people who would otherwise be homeless.

“This is one place you can’t ignore them, because you actually see how they live,” Spyder says, gesturing around his camp. “You have the Slabs everywhere you go. If you go to New York, Boston, San Diego, wherever, you have these types of people there in the cities, too. You just choose to ignore them.”

A well-oiled machine

On the northern perimeter of Slab City, dirt roads lead to a dusty art commune called East Jesus. The camp may look fairly similar to other parts of the Slabs, with eccentric art installations made of repurposed garbage and provisional trailer accommodations for a small group of residents, but the area is private property. Local non-profit the Chasterus Foundation bought the 30-acre plot in 2016.

East Jesus’ main attraction is an elaborate outdoor “art museum” that’s open to the public year-round, featuring a wall of broken TVs covered with pithy messages, a car adorned with baby doll heads, and other oddities. Behind the museum is where East Jesus residents actually live, in an intricate maze of trailers surrounding a communal living area.

Pyro Iskaki, a burly, tattooed caretaker of the art commune, gives me an impromptu tour of the camp’s infrastructure, leading a pitbull on a leash around with him. Partly because of its smaller size and private status, East Jesus is a well-oiled machine. There’s a battery bank, a backup diesel generator, composting toilets, a water heater, a hand-washing station, a library, a pantry, and a recycling area.

Now, East Jesus is hoping to expand some of those community practices into the Slabs. Iskaki says he’s working on accessing county and state grants so dumpsters can be brought out to Slab City to help alleviate its growing trash problem.

“[We’re hoping to] get it to something more livable,” he says. “Because there are a lot of people out here who have become accustomed to the filth because they don’t have a choice.”

But in trying to implement structured programs in a self-proclaimed “lawless” place, Iskaki admits East Jesus has gotten some negative feedback from those in the Slabs. “There are some people that believe we’re gentrifying the Slabs,” he says. “But we’re not trying to create structure for the Slabs. We’re trying to offer a resource to the community to be able to improve itself and take some responsibility.”

While there are disagreements over what an ideal Slab City should look like, most of the residents came here seeking the same sense of independence. The town may not actually be lawless—in fact, the Slabs are regularly patrolled by local police officers—but after seven decades, it still offers certain freedoms that are difficult to find elsewhere.

Spyder, for one, credits the existence of his mini desert empire to the anarchic nature of Slab City. “In a big city I could never own anything like this,” he says. “They have too many laws about what to do, what not to do. Out here nobody tells me what to do.”