No one writes love letters about August in New York City. The city of asphalt and glass towers is a greenhouse without the green; skyscrapers suffocate, sidewalks sizzle, and the subway feels (and smells) like a dog’s mouth. It’s no mystery why people flock to water when temperatures soar. City dwellers have always found solace just north of New York in the Hudson River Valley.

I escape the hot and humid city early on a Sunday morning in August and hop on a Metro North train bound for Beacon, New York. In less than two hours, I’m boarding a small boat filled to capacity with 40 other people headed to Pollepel Island, located 1,000 feet from the eastern bank of the Hudson River. Our destination is not so much the island itself—which is rocky and wild—but a site that is familiar to anyone who has ridden the Metro North’s Hudson line, hiked a trail in the Hudson Highlands, or kayaked in the brackish waters of the Hudson: Bannerman’s Castle.

The 30-minute boat ride to Pollepel—often referred to as Bannerman’s Island—is a blissful respite from the afternoon heat. The views of both sides of the Hudson are beautiful but mostly uneventful—until I spot the remains of Bannerman’s Castle rising like a decorative, concrete Phoenix from the lush vegetation on its island home. People scramble to take photos and our boat slows down as we approach, stopping entirely for 20 minutes as we wait for kayakers to paddle away from the dock (in 2015, a man died when his kayak overturned near the island and his fiancée pleaded guilty to criminally negligent homicide).

New York State bought the island in 1967 and it currently belongs to the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation. Since 1994, nonprofit Bannerman Castle Trust has worked in conjunction with the Parks Department to maintain the castle. The Trust gives weekend tours, hosts movie nights, and other events on the island from May through October.

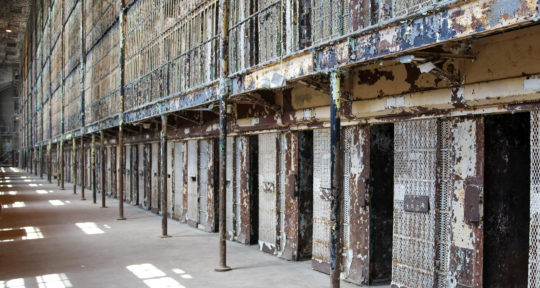

After finally docking, we walk up 72 steps to the island’s original walkway, and the castle ruins rise stoically to our left. Visitors aren’t allowed to get too close to the castle now for safety reasons, but we aren’t missing out on much—even when the castle was complete, the inside was downright boring compared to its flashy exterior.

The Bannerman business

The origins of this fairytale-like structure are surprisingly humble. Despite its fantastical appearance and isolated location, no pirates or princesses were involved in its construction. In fact, it was built for a rather banal purpose: as a storage facility for a New York City-based military surplus business. Visitors approaching from the north can still make out the words “Bannerman’s Island Arsenal” cast in concrete on one of the castle’s remaining walls.

Francis Bannerman VI was born in Northern Ireland in 1851. Three years later, he emigrated to the U.S. with his parents, and the family settled near the Brooklyn Navy Yard. His father left to fight in the Civil War and Bannerman picked up jobs as a messenger and a courier to help support his family. When he was just ten years old, Bannerman started his own business refurbishing wares he had dredged out of the Hudson River and selling them back to the sailors who had thrown them overboard in the first place.

Four years later, Bannerman’s father—who had been wounded in battle—joined his son’s burgeoning business. Bannerman would eventually break off from his father and open a competing store nearby, but the father admired Bannerman’s business sense, acknowledging that competition was good for both businesses.

Although Bannerman was a shrewd businessman, he was really a collector at heart. In 1897, he opened a seven-story military surplus store on Broadway in New York City; the bottom floors were for his retail business and the top floor housed a museum. He was fond of saying that “Bannerman’s could outfit an army in a week—10,000 rifles, 10,000 saddles no problem,” and had the inventory to prove it.

After the Spanish-American War, Bannerman purchased 90 percent of the Spanish arms, including 30 million rounds of live ammunition. According to our tour guide, Pat, the city wasn’t too thrilled with Bannerman’s new acquisition, telling him: “Don’t even think about bringing this stuff within city limits.”

A sketch on scrap paper

In 1900, millions of people traveled upstate either by boat or passenger train along the Hudson, and Bannerman and his wife, Helen Boyce (whom he married in 1872), were two of them. When Bannerman spotted Pollepel Island and decided it was the perfect home for his new storage facility, Helen, citing the island’s rocky terrain, replied, “I think you’re crazy.”

Undeterred, Bannerman purchased the island for $1600 (about $50,000 today). In 1901, he used his own black powder to blast a section of the island level, then erected his first warehouse, a plain concrete building, upon which he hung a large banner advertising his Broadway store. His “crazy” idea worked: Those millions of eyes traveling on the Hudson translated into a business boom and Bannerman dreamed of building something even more eye-catching.

In a nod to his Scottish heritage, Bannerman decided that his next warehouse would resemble a castle. Built by day laborers—and without architects, engineers, contracts, or blueprints—the castle was designed by Bannerman himself, sketched on whatever scrap paper he had on hand. “He wasn’t just the boss and the brains, he got his hands dirty,” says Pat.

The building was imagined without a single right angle and historians have speculated that Bannerman was utilizing an old theatrical trick where structures are built as parallelograms, creating the illusion of a taller structure. Ever the businessman, this was also a way to—literally, and figuratively—cut corners, giving Bannerman “more bang for his buck,” says Pat.

Bannerman’s Castle had everything you would expect of a proper castle, including terraced gardens, a dry moat full of thistle plants, a drawbridge, a portcullis (a heavy, vertically-closing gate made with metal spikes), and a promenade around the island’s perimeter made from sunken barges. While the main castle functioned strictly as a warehouse, the Bannermans constructed a smaller structure nearby in 1908 to use as a summer home for themselves and special guests.

Today, the summer home has been restored and functions as a small museum, visitor center, and gift shop. Bannerman loved details and added military motifs into the structures everywhere he could. Shamrocks and thistles are homages to Scotland, and each fireplace was handcrafted to include a different Biblical saying.

According to Pat, Bannerman believed that “any man who owns an island and a castle should have a crest,” so he designed his own, including symbols depicting his family’s heritage and his business interests.

The castle crumbles

On a hot day in 1920, Helen was relaxing in a hammock when she got up to grab a drink. While she was in the kitchen, a powder house on the island—full of live artillery shells—exploded. No one knows exactly how it happened and no one was hurt, but the blast was heard from 50 miles away and broke windows on both banks of the Hudson River. When Helen returned to her hammock, she found a huge chunk of concrete where she had sat just minutes before.

“She would’ve been a goner had she not gotten thirsty at the right moment,” says Pat. Bannerman died in 1918, but his wife continued to visit the island until the early 1930s. It took three full days to remove concrete debris from nearby railroad tracks, but the castle’s damaged roof and windows were never repaired.

Helen died in 1931 and the Bannermans are buried with their children in a family plot in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. In the 1950s, the island was put up for sale by descendents of the Bannermans, who were no longer interested in maintaining the family business. They hired a munitions expert to clean out the remaining supplies, and the Smithsonian was invited to take a look at the collection, which included weapons from ancient Zulu warriors and the Bronze Age. It’s estimated that 50 percent of the cannons scattered around the U.S. today came from Bannerman Island.

Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

In August 1969, a huge fire began on the island and burned for three days. It could be seen up to 35 miles away, and again, no one knows exactly how it started. The interior of the castle—made of wood treated with kerosene—was completely destroyed. The shell remained standing over the years while the summer house was stripped by vandals and battered by storms. In December 2009, a heavy wet snow fell in the Hudson Valley and about 50 percent of the castle—including the entire front and half of the east wall—collapsed overnight.

Much of the island is overgrown now. Bannerman may have been able to tame it temporarily with his weapons of war, but nature has been slowly (and sometimes explosively) reclaiming it ever since. Colorful blooms dot the landscape thanks to a Wednesday morning garden club, and even with the poison-ivy covered ruins looming in the background, it’s not hard to see why the Bannermans were charmed by this 6.5-acre oasis 50 miles—and a world away—from the city.

Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

It took the Bannerman Castle Trust four years to raise money for the six supports that are currently holding up what remains of the grand structure, and they have no plans to restore it any further. In 1962, Bannerman’s grandson, Charles, wrote, “No one can tell what associations and incidents will involve the island in the future. Time, the elements, and maybe even the goblins of the island will take their toll of some of the turrets and towers, and perhaps eventually the castle itself, but the little island will always have its place in history and in legend and will be forever a jewel in its Hudson Highland setting.”

If you go

Guided and self-guided tours of Pollepel Island are available on weekends, May through October. Boats depart from Beacon or Newburgh.