McDougall-Hunt is a residential neighborhood on Detroit’s east side; it’s dotted with burned-out husks of houses that have succumbed to fire either by arson or accident. But the area, specifically the 3600 block of Heidelberg Street, is increasingly on both tourists’ and local community members’ itineraries.

The block is overcome with found art, collected and designed by Tyree Guyton. Guyton, who grew up in what is now known as the Dotty Wotty House, started the Heidelberg Project in 1986, when he returned home and was shocked at the desecration, racism, and violence he witnessed in his hometown.

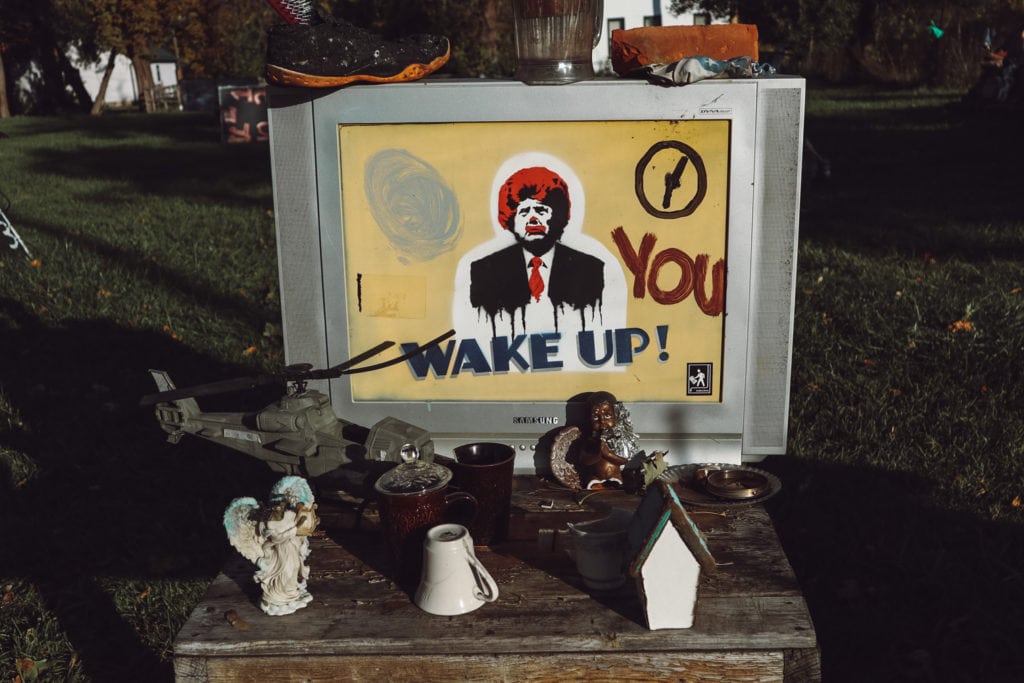

Alongside his Grandpa Mackey, Guyton began rearranging Heidelberg Street with found objects, like abandoned teddy bears, old TVs, and broken-down cars, creating beauty from wreckage. Guyton wanted to make a statement. He wanted to reclaim his neighborhood, and make it a safe space for kids and families to gather.

In the more than three decades since its birth, the Heidelberg Project has had a tumultuous history—and as I park my car on Heidelberg Street, I’m curious to see how the project has changed over the years.

Constantly evolving

The Heidelberg Project has been controversial in Detroit since its inception. It was dismantled twice in the 1990s by people serving in the Detroit government, who thought the project drew attention to the city’s struggles with urban blight. In 2013, 2014, and even as recently as 2019, the project and its surrounding buildings have been victim to more than a dozen arson attacks.

But in the last decade, the local community—and more recently, the local government—has banded together to support the Heidelberg Project. Not only has Guyton been recognized nationally and internationally as the founder of one of the world’s greatest contributions to public art, but the modest project infuses Detroit proper with approximately $2.4 million in tourist revenue per year.

In the face of arson, demolition, and see-sawing Detroit politics, the Heidelberg Project has continued on, constantly evolving, and it often incorporates these obstacles into its artistic story.

Public art in a pandemic

When I visit, it’s a cold morning in late 2020, a year during which I faced unemployment, family death due to COVID-19, and separation from loved ones. Earlier in the year, Detroit’s streets—like so many others in the country—were filled with Black Lives Matter protests. I walk the Heidelberg Street sidewalks and wonder what I can learn from their constant evolution.

This is my fourth visit to the Heidelberg Project over as many years. The last time I was here was a blustery October weekend in 2019. Guyton’s sister, Melody Guyton, was volunteering as a docent on the street across from the Dotty Wotty House, where she grew up and currently lives.

I remember her friendly, mask-less face and how we walked through the installations together, without a thought to the trajectory of airborne particles leaving each other’s mouths.

This morning, I have a mask in my pocket just in case I cross paths with another person, even though the project is entirely outdoors. In-person tours of the Heidelberg Project were canceled in March, 2020, but I’ve taken the advice on the project’s website and downloaded an app to help guide my pandemic-era exploration. The app was designed in 2018 and won a MediaPost Appy Award, according to Heidelberg Project Program Director Margaret Grace.

“We have experienced more visitors than expected since the beginning of the pandemic,” Grace says in an email. “The art environment has served as a destination for those who are looking for something fun and safe to do outdoors.”

Outdoor art through an app

Using the GPS-based app to guide me, I weave through the various installations: A hot pink hummer peeps out from the grass where it’s half buried. Shoes, which symbolize souls (“soles”), are strung along fences and trees. Abandoned cars are bursting with found dolls.

According to the app, one installation—a pile of shoes topped with a plastic angel—is called Haiti. To Guyton, the shoes represented all those who died in Haiti’s 2010 earthquake. New in 2020 is a disposable white mask covering the angel’s face.

Clocks, and specific times, are another motif scattered throughout the Heidelberg Project. The asphalt street and sidewalks are painted with clocks and timestamps. I weave through trees nailed with more clocks, and signs that ask, “What time is it?”

According to the app, the clock motif became more prominent after the 2013 arson attacks and “reflect that it is time for change.” Grace says, “The clocks are in reference to our perception of time. What you take from that is up to you to decide.”

If you go

The Heidelberg Project is free and open to the public from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. daily. You can park along the street, but remember it is a residential area so be respectful, and do not photograph residents. The Heidelberg Project App can be downloaded via the App Store or Google Play. In-person tours for spring/summer 2021 can also now be scheduled here.