Thomas Sewid is providing a crash course in supernatural beach safety. The subject is Pokwus, a small, green cryptid (a creature whose existence has not been scientifically proven) found on rural beaches. As his wife Peggy dances around the room in mossy garb, wearing a striped mask with a brilliant teal nose, he emphasizes that the Pokwus represent temptation—and that one must never accept what they offer, be it shellfish or cigarettes. This was not exactly what I’d expected to hear about Bigfoot, but, as I was fast learning, the cryptid is versatile.

While many Bigfoot-themed gatherings fill entire hotels, the Marblemount Sasquatch Conference takes place in the Washington town’s community club, a convivial space with one large main room and a tree-ringed meadow behind it. The festival began in 2019, but according to its founder, Syvella Kalil, the idea had been percolating for years.

“People here in this town were talking to me, saying, ‘They [Sasquatches] are here,’” she says.

Given the terrain, it’s unsurprising. Marblemount sits in the Cascade Mountains, 2 hours northeast of Seattle. Dense forests of towering pines sweep up toward craggy mountains, while cold, clear rivers, tinged green from glacial runoff, flow nearby. This is the home of the famously rugged North Cascades National Park, and the towns scattered in its shadow tend to be small and outdoor-oriented. In other words, it’s an ideal venue for Bigfoot.

A Woo event

The Marblemount conference is considered more of a “Woo” event. In the Bigfoot community, the term refers to the belief that Sasquatches are metaphysical beings. Although their physical descriptions of Bigfoot often match those of “apers” (another subset who believe the cryptids are variants of prehistoric apes), Woo proponents believe that the creatures also possess supernatural traits, such as shapeshifting and telepathy. Even within this small subset, there are distinct variations in personal experiences—and regardless of whether one fully believes the stories, they offer fascinating perspectives to consider.

It’s interesting to see a roomful of Sasquatch enthusiasts because the subculture is, by its very nature, somewhat isolated. After all, Bigfoot doesn’t just hang around the Walmart parking lot. Here, people who spend most of the year either physically or ideologically isolated (or both) can finally come together. Camouflage-clad locals clutch binders of photos detailing their own encounters, a pair of sisters has seen enough Bigfoot shows to want to learn more, and a young man says he saw a mysterious figure on Halloween night. There are soldiers from an army base a few hours away, and several groups that look as if they’ve just arrived from Seattle. And all of them are listening intently to Sewid.

Growing up, Sewid says he was called “Tommy 10,000 Questions,” because of his boundless curiosity, especially regarding Sasquatch. As a member of the Kwakwaka’wakw tribe of British Columbia, Sewid has always had a deep cultural connection to Sasquatches in all of their forms, from Pokwus, to the taller, shaggier, more familiar figures in folklore. They have been depicted in art and stories for millennia, even taking places of honor on ceremonial totem poles and family crests.

As an adult, Sewid spent many years living in the Canadian bush, where he says he encountered Sasquatches of all shapes and sizes. “You see things, hear things, smell things, and always feel like you’re being watched,” he says. “If you stay in the bush long enough, you will see Sasquatch.”

Sasquatch scribe

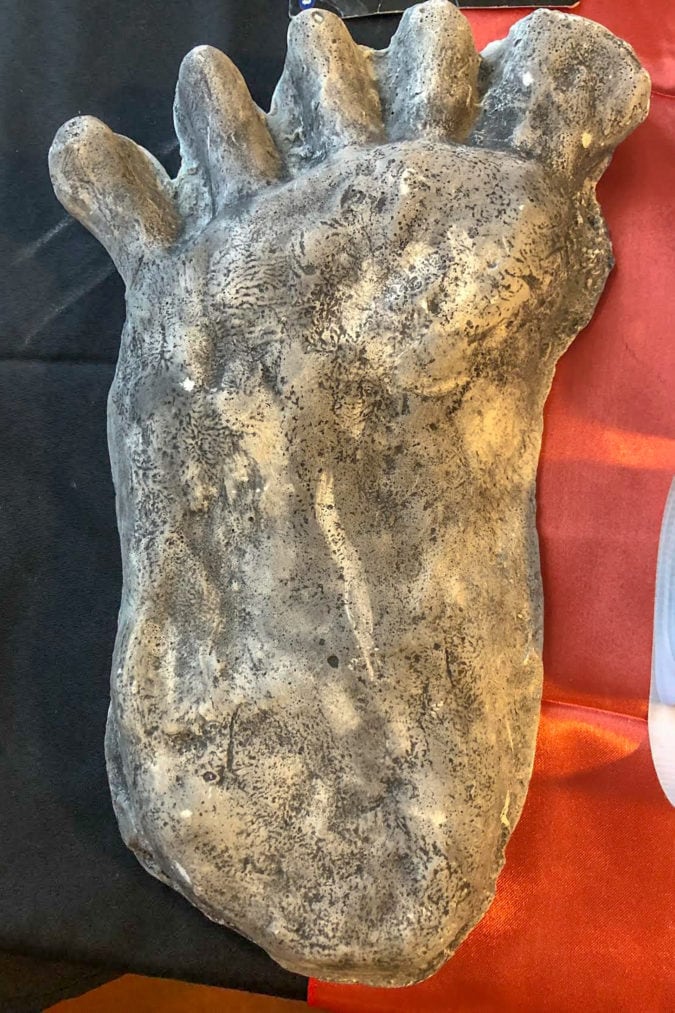

Dr. J. Robert Alley’s first Bigfoot encounter occurred during a camping trip on Vancouver Island in 1975. He spent years investigating police reports of Sasquatch sightings and has interviewed individuals from more than 45 Indigenous tribes about their own Sasquatch experiences. While he speaks about the interdimensional capabilities of Sasquatch, he also focuses on physical artifacts. Holding up a cast of a footprint, he points out the width of the foot itself, and the dexterity of the toes—more ape than human, but not quite either one.

Dr. Alley praises the conference as an opportunity to exchange ideas and experiences. “People will share things with you that help you fill in pieces of your puzzle,” he says.

For Judy Carroll, the Sasquatch relationship is that of a teacher and student. She originally got interested in Bigfoot expeditions through various TV programs, but quickly became bored with the standard, science-based approaches. “I set out with the intention of having a meaningful relationship [with Sasqautch],” she says. Eventually, Carroll says she met an 8-foot-tall individual named Khombe, who could also manifest as orbs of energy. After years of interacting with him, she has come to see Sasquatches as spiritual teachers who reveal emotional and psychological truths to their students.

“It’s not about who they are, it’s about who you are,” she says.

Carroll was mentored in her process by Thom Cantrall, a longtime fixture in the Pacific Northwest Sasquatch community. He first got interested in his teens, and says he had frequent Sasquatch sightings during the time he spent working as a logging engineer in the Olympic Peninsula. He met his own Sasquatch teacher, with whom he says he communicates telepathically, in 2010. Cantrall has also written 12 books on Bigfoot. “That’s my job, being their scribe,” he says. “Whenever they need something written, I get a visit.”

The Bigfoot business

A love of nature is a common thread among Sasquatch enthusiasts, and many of them see the figures as environmental teachers. All four of the conference’s speakers spent extensive time in the backwoods, and the issues that they say enrage Sasquatches are the same ones that humans are grappling with: fracking, deforestation, and declining salmon populations. There’s a sense that we could all be more like Sasquatches, if only we were more willing to embrace our spiritual sides and delve into the wilderness while still respecting it. As Carroll puts it, cryptids teach humans “reverence for trees, nature, and each other.”

Bigfoot is also big business. Outside the community center, vendors offer wind chimes, stickers, and t-shirts celebrating the cryptids. Sasquatch tours are also growing in popularity. Sewid’s company, Sasquatch Island, hosts tours tailored to individual interests. While many take place in the wilderness, he also hosts “urban tours,” exploring sightings near towns and homes. Having worked as a hunting and whale watching guide, Sewid sees potential for Bigfoot tours to eventually fill a similar niche in the outdoor industry. “A lot of these people, they’re putting their heart and soul into it,” he says.

Carroll is still working on developing her company, Heart of the Hoh, which will offer Sasquatch expeditions with a spiritual component. Long before she began looking for Bigfoot, she fell in love with the Hoh Rainforest, known for its ethereal landscapes of mosses and ferns. While Sasquatch sightings would be a goal, she also plans to focus on her clients’ personal growth as they explore the forest.

“I want to help people reconnect with themselves and with nature,” she says.

For Kalil, it’s always been about fostering community—both the temporary one at the conference, and the more physical one of the town itself. Like so many of its neighbors, Marblemount’s tourism industry is largely seasonal, and she hopes that events like these will draw more visitors year-round, while simultaneously promoting the cryptids. For her, it’s not just about making money: “It’s about getting the word out,” she says.